|

Chronology

INDIA

TEXTS, QUOTATIONS, ILLUSTRATIONS

INDIA, CHINA, JAPAN - and The WEST

A Chronological Panorama - 12 Reloaded

Web Pages from the Previous Website Version

Welcome to A 1000s of Years' History Odyssey!

HINDUISM

ADVAITA VEDANTA PHILOSOPHY

and EARLY INDIAN BUDDHISM

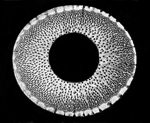

c. 2600 BCE:

Square seal depicting a nude male dëity with three faces,

seated in yogic position on a throne.

Harappan Bronze Age Culture, c. 2600-1900 BCE.

Dimensions: 2.65 x 2.7 cm, 0.83 to 0.86 thickness.

Excavated at Mohenjo-daro, present-day Punjab, Pakistan.

Now in the Islamabad Museum.

Source: https://www.harappa.com/indus/33.html

BRĀHMAN - "The highest Universal Principle", "The Ultimate Reality in the universe"

ब्राह्मण

ĀTMAN - "The Essential Self"

आत्मन

c. 1500 - c. 900 BCE - The Veda Era:

"That One breathed breathlessly by Itself;

other than It there nothing since has been."

Quoted from the Rigveda, X, 129. Trsl. by R.H. Blyth, 1960, Vol. I.

c. 1200 - c. 1000 BCE:

SAMĀDHI - " ... a state of meditative consciousness.

It is a meditative absorption or trance, attained by the practice of dhyāna.

समाधि (Sanskrit)

c. 1000 - c. 700 BCE - The Upanishad Era:

TAITTIRYA ARANYAKA

"The blind one found the jewel;

The one without fingers picked it up;

The one with no neck put it on;

And the one with no voice praised it."

In the Taittirya Aranyaka. Trsl. by R.H. Blyth, Vol. I.

ADVAITA - "Not Dual", "Non-Duality", "Non-Division"

अद्वैत (Sanskrit)

Date: 8th to 6th CENTURY BCE

AUM / OM

ॐ

DHYANA - "Meditation", "Thinking"

ध्यान (Sanskrit) -

झान (Pali)

CHANDOGYA UPANISHAD

"Part One - Chapter I — Meditation on Om"

1. The syllable Om, called the Udgitha, should be meditated upon;

for people sing the Udgitha, beginning with Om.

Now follows the detailed explanation of the syllable:

2. The essence of all these beings is the earth;

the essence of the earth is water;

the essence of water is plants;

the essence of plants is a person;

essence of a person is speech;

the essence of speech is the Rig—Veda;

essence of the Rig—Veda is the Sama—Veda;

the essence of the Sama—Veda is the Udgitha which is Om.

"PART 7 - Chapter VI — Meditation as Brahman"

1. "Meditation (Dhyana) is, verily, greater than consideration.

Earth meditates, as it were.

The mid—region meditates, as it were.

Heaven meditates, as it were.

The waters meditate, as it were.

The mountains meditate, as it were.

The gods meditate, as it were.

Men meditate, as it were.

Therefore he who, among men, attains greatness here on earth seems to have obtained a share of meditation.

Thus while small people are quarrelsome, abusive and slandering, great men appear to have obtained a share of meditation.

Meditate on meditation.

2. "He who meditates on meditation as Brahman, can, of his own free will, reach as far as meditation reaches

— he who meditates on meditation as Brahman. - - -"

Trsl. by Swami Nikhilinanda.

Link to Swami Nikhilinanda's English translation of the Chandogya Upanishad:

http://swamij.com/upanishad-chandogya.htm

"The word zen, dhyana, appears first in the Chandogya Upanishad, and means "thinking," or rather,

"meditating," the difference being all-important, for Zen means thinking with the body. - - - "

R.H. Blyth, 1960.

Date of Chandogya Upanishad, part of the Sama Veda:

Variously dated between the 6th and 8th centuries BCE.

5th CENTURY BCE:

"His heart is with Brahman,

His eye in all things

Sees only Brahman

Equally present,

Knows his own Atman

In every creature,

And all creation

Within that Atman."

In the Bhagavadgita. Trsl. by R.H. Blyth, Vol. I.

ADVAITA VEDĀNTA

"Aum is verily the beginning, middle and end of all Knowing.

Aum as such, one, without doubt, attains immediately to that (the Supreme Reality)."

"One who has known Aum which is soundless and of infinite sounds and which is ever-peaceful on account of negation of duality is the (real) sage and none other."

"That which has no parts (soundless), incomprehensible (with the aid of the senses), the cessation of all phenomena, all bliss and non-dual Aum,

is the fourth and verily the same as the Ātman.

He who knows this merges his self in the self."

Māndūkya Upanishad Kārikā (commentary) by

Gaudapāda,

composed around the year 0. Trsl. by Swami Nikhilananda, 1936.

"This realization of non-duality is the end to be attained."

From Shankara's introduction to the Māndūkya Upanishad

Kārikā by Gaudapāda, 8th century CE

Trsl. by Swami Nikhilananda, 1936.

"Vedānta certainly does not help us to bring grist to our individual mill.

It certainly does not tell us how to increase our capacity to enjoy the pleasures derived from material objects.

But Vedānta really teaches us how to enjoy this world after realizing its true nature.

To embrace or comprehend the universe after realizing it as the non-dual Brahman,

gives us peace that passeth all understanding."

Swami Nikhilananda in the preface for his translation of the

Māndūkya Upanishad, 1936.

BUDDHISM

BRĀHMAN - "The highest Universal Principle", "The Ultimate Reality in the universe"

ब्राह्मण

ĀTMAN - "The Essential Self"

आत्मन

5h Century BCE:

ANĀTMAN - "The Not-Self"

अनात्मन् (Sanskrit)

ADVAYA - "The Essential Nature of Things when truly understood, according to Buddhist thought":

अद्वय (Sanskrit)

- "not two without a second", "only", "unique", "non-duality", "ultimate truth", "identity", "unity"

DHARMA - The "Law" in Buddhist thought

धर्म (Sanskrit) -

धम्म (Pali)

SIDDHĀRTHA GAUTĀMA BUDDHA - c. 563-483 BCE, alt. c. 480-400 BCE

拈華微笑

NEN-GE-MI-SHŌ - llt. "Pick up Flower, Subtle Smile"

In a famous, though legendary, wordless sermon of his, Buddha is reported to have shown his diciples a flower - however, only Mahākāśyapa understood ...

Buddha commented, "I possess the true Dharma eye, the marvelous mind of Nirvana, the true form of the formless,

the subtle [D]harma [G]ate that does not rest on words or letters but is a special transmission outside of the scriptures. This I entrust to Mahākāśyapa."

This central Zen Buddhist anecdote was composed much later, possibly by Chinese Ch'an Buddhists. Earliest reference is dated 1036.

Sources: Dumoulin, 2005, p. 9, Harmless, 2008, p. 192

& https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Flower_Sermon

SHŪRANGAMA SAMĀDHI SŪTRA

"Buddha said, 'The sound of the bell continues during a space of time;

How do we become conscious of it?

Does the sound come from the ear, or the ear go to the origin of the sound?

If it does not go (one way or the other) there is no hearing.

For this reason, it must be understood, that hearing and sound are neither special.

We mistakenly put hearing and sound in two (different) places.

Originally it is not a matter of cause and effect or of natural law."

Shūramgama Samādhi Sūtra. Trsl. into Chinese by Kumārajiva,

344-413 CE Quoted by Wu-men Hui-k'ai (Jap.: Mumon Ekai),

1183-1260, in the Wu-men-kuan (Jap.: Mumonkan).

Trsl. by R.H. Blyth, Vol. IV.

" - - - Ananda, listen again to the drum being beaten in the Jeta Garden when the food is ready. The assembly gathers as the bell is struck.

The sounds of the bell and the drum follow one another in succession.

What do you think? Do these things come into existence because the sound comes to the region of the ear, or because the ear goes to the place of the sound?

Again, Ananda, suppose that the sound comes to the region of the ear. Similarly, when I go to beg for food in the city of Shravasti, I am no longer in the Jeta Grove.

If the sound definitely goes to the region of Ananda's ear, then neither

Maudgalyana nor Kashyapa would hear it, and even less the twelve hundred and fifty shramanas who, upon hearing the sound of the bell, come to the dining hall at the same time.

Again, suppose that the ear goes to the region of the sound. Similarly, when I return to the Jeta Grove, I am no longer in the city of Shravasti. When you hear the sound of the drum,

your ear will already have gone to the place where the drum is being beaten. Thus, when the bell peals, you will not hear the sound - -

even the less that of the elephants, horses, cows, sheep, and all the other various sounds around you.

If there is no coming or going, there will be no hearing, either.

Therefore, you should know that neither hearing nor sound have a location, and thus the two places of hearing and sound are empty and false.

Their origin is not in causes and conditions, nor do their natures arise spontaneously.

- - -

Moreover, Ananda, as you understand it, the ear and sound create the conditions that produce the ear-consciousness.

Is this consciousness produced because of the ear such that the ear is its realm, or is it produced because of sound, such that sound is its realm?

Ananda, suppose the ear-consciousness were produced because of the ear. The organ of hearing would have no awareness in the absence of both movement and stillness.

Thus, nothing would be known by it. Since the organ would lack awareness, what would characterize the consciousness?

You may hold that the ears hear, but when there is no movement and stillness, hearing cannot occur.

How, then, could the ears, which are but physical forms, unite with external objects to be called the realm of consciousness?

Once again, therefore, how would the realm of consciousness be established?

Suppose it was produced from sound. If the consciousness existed because of sound, then it would have no connection with hearing.

Withour hearing, then the characteristic of sound would have no location.

Suppose consciousness existed because of sound. Given that sound exists because of hearing, which causes the characteristic of sound to manifest,

then you should also hear the hearing-consciousness.

If the hearing-consciousness is not heard, there is no realm. If it is heard, then it is the same as sound. If the consciousness itself is heard,

who is it that perceives and hears the consciousness? If there is no perceiver, then in the end you would be like grass or wood.

Nor is it likely that the sound and hearing mix together to form a realm in between. Since a realm in between could not be established,

how could the internal and external characteristics be delineated?

Therefore, you should know that as to the ear and sound creating the conditions which produce the realm of the ear-consciousness,

none of the three places exists. Thus, the ear, sound, and sound-consciousness - - these three - - do not have their origin in causes and conditions, nor do their natures arise spontaneously. - - - "

Shūrangama Samādhi Sūtra. Trsl. into Chinese by Kumārajiva,

344-413 CE. Primary translation by Bhikshuni Heng Ch'i.

2nd - 3rd CENTURIES CE:

NĀGĀRJUNA - c. 150 to c. 250 CE:

शून्यता

ŚŪNYATĀ - "Non-Substantiality", "Non-Self", "Voidness", "Non-Duality"

sarvaṃ ca yujyate tasya śūnyatā yasya yujyate

sarvaṃ na yujyate tasya śūnyaṃ yasya na yujyate

"All is possible when Emptiness is possible.

Nothing is possible when Emptiness is impossible."

Quotation from Chapter 24, verse 14, in the Mūlamadhyamakakārikā.

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nagarjuna

शून्यता - ŚŪNYATĀ

-

空 - KŪ

"Kū: (Skt.: shūnya or shūnyatā)

A fundamental Buddhist concept, variously translated as non-substantiality, emptiness, void, latency, relativity, etc.

The concept that entities have no fixed or independent nature.

The idea is closely linked to that of dependent origination (Skt.: pratîtya-samutpâda, Jap.: engi],

which states that, because phenomena arise and continue to exist only by virtue of their relationship with other phenomena,

they have no fixed substance and have as their true nature kū.

The concept of kū thus teaches that nothing exists independently. Its practical implications lie in the rejection of attachments to transient phenomena,

and to the egocentricity of one who envisions himself as being absolute and independent of all other existences.

It is an especially important concept in Mahayana Buddhism.

On the basis of sutras known as Hannya (Skt.: prajna) or Wisdom sutras, the concept of kū was systemized by Nâgârjuna,

who explains it as the Middle Way, which here means neither existence nor non-existence.

- - - "

In: A Dictionary of Buddhist Terms and Concepts.

Matsuda Tomohiro, chief editor.

T.O. comment: The south-Indian Mahayana scholar Nāgārjuna is

thought to have lived between 150 and 250 CE. His systematization of

the doctrine of Non-substantiality, or 'Shūnyatā' [Jap.: 'kū'], was set

forth in his treatise 'Mahāprajnāpāramitā-shāstra', a commentary on

the Makahannya Haramitsu sutra. The treatise was translated into

Chinese by Kumārajiva around 405 CE. Also referred to as the

'Middle' way, Nāgārjuna's doctrine is integral to Mahayana

Buddhism, and he is revered as the founder of the eight sects:

Kusha, Jōjitsu, Ritsu, Hossō, Sanron, Kegon, Tendai and Shingon.

|

|