|

1665-1675?: The Kyotaku denki Fairy Tale is Born?

Shinchi Kakushin, Kichiku, Kyochiku & Kyōto Myōan-ji

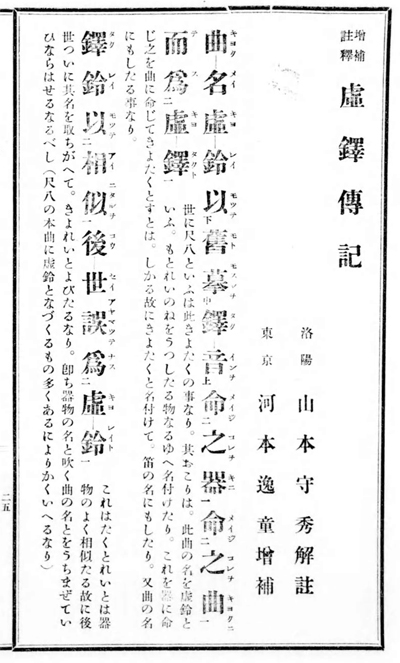

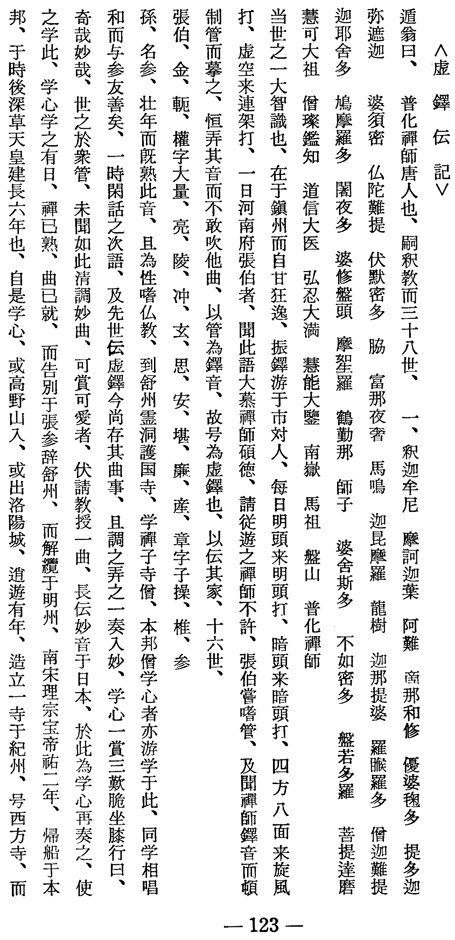

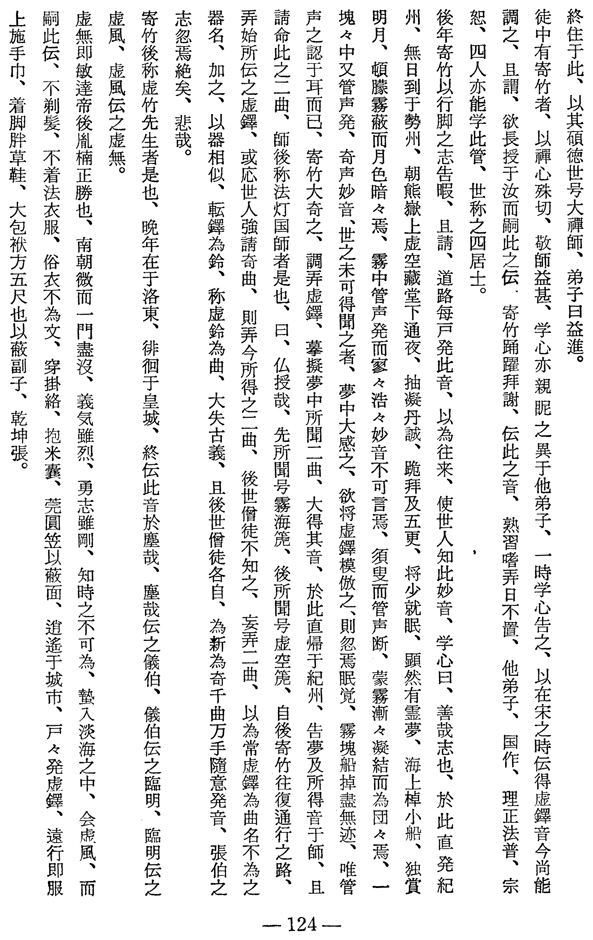

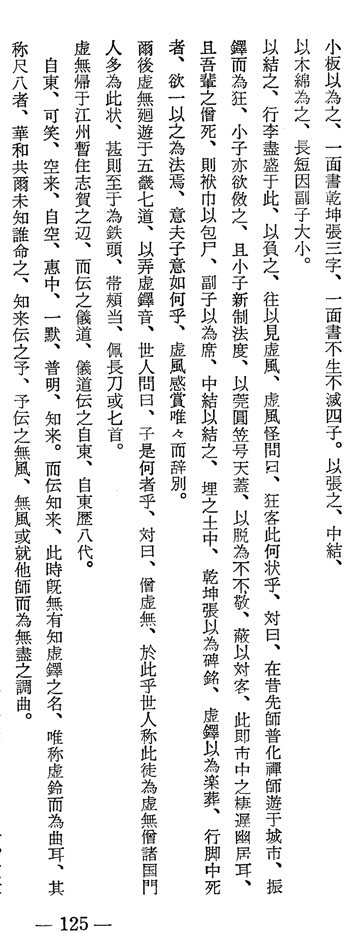

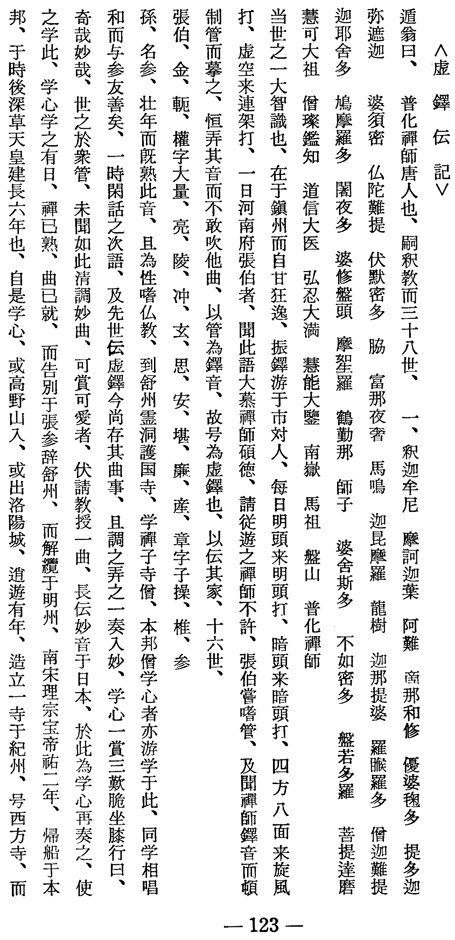

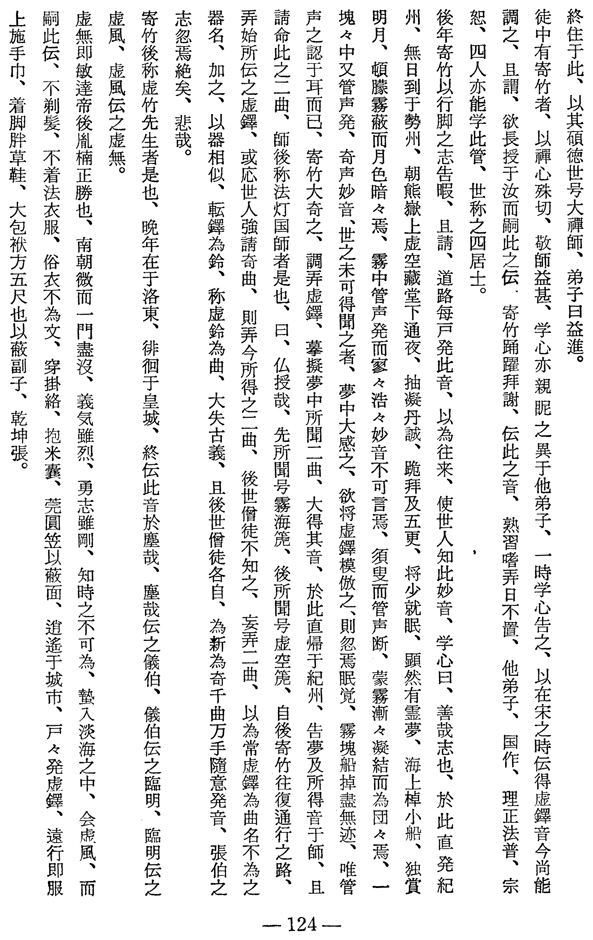

虚鐸伝記 - Kyotaku denki

"Record of the History of the Imitated (or, False) Bell"

WARNING! The Kyotaku denki narrative is complete fabrication that cannot be taken seriously as trustworthy "historical fact" in any way.

Actual authorship unknown. No exact date of actual first completion.

Some basic elements of the fabricated tale were probably created by mid- to late17th century early Kyōto 'Komusō' beginning during the late 1660s

and the early 1670s.

Source: Complete text reprinted in Nakatsuka 1979, pp. 123-125 - see scanned pages in the below.

Besides, one edition of the text can be found in an early 20th century Japanese publication preserved at the Japanese National Diet Library in Tokyo,

and in 1981 the original version of the Kyotaku denki was made available in a book edited by Kowata Suigetsu - more info below.

IMPORTANT INITIAL CLARIFICATIONS:

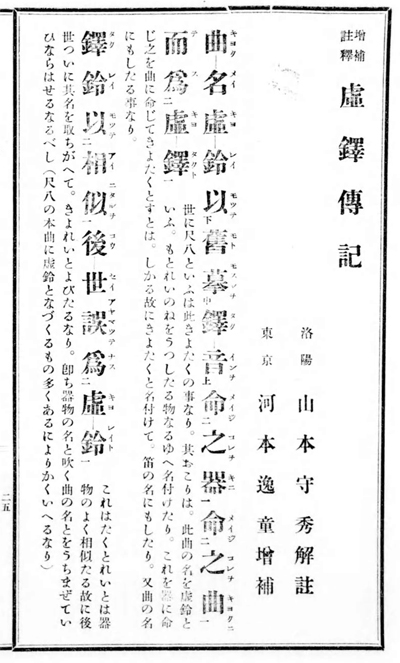

First of all: The presumably "original" Kyotaku denki text, that was edited and published in reprint by Yamamoto Morihide in Kyōto,

in the Kyotaku denki kokujikai,

虚鐸傳記国字解 in 1795, is not mentioned, nor quoted, in any other preserved

and available Japanese text dating from before that year.

It is not known to what extent, and how, the text and subject matter of its narrative was ever actually disseminated neither within 'Komusō'

circles themselves - nor to the general, wider public. That is to say, more precisely: During the Edo Period that ended in 1868,

and the eventual 'Komusō' prohibition in late 1871.

The term 'Fuke-shū',

普化宗

"Fuke Sect", is completely absent in the original Kyotaku denki tale.

In other words: There was not any "Fuke Sect" to mention at all, when the Kyotaku denki phony text was once created!

The earliest known 'Komusō' document issued by the 'Reihō Temple, the "Temple of the Law of the Bell", is dated 1677: Enpō year 5, the 6th month -

which, NB, is about half a year older than the infamous 'Enpō 5 Oboe' Memorandum of January 11, 1678!

Therefore, we should presume, that the part of the Kyotaku denki, that focuses so heavily on the central ideological importance of the ringing of Fuke's Bell,

and legendary Kichiku's experience with the moon, the 'honkyoku' 'Mukaiji', would certainly have been in existence before 1677?

Likewise, with both the two main "temples" Kyōto Myōan-ji and Ichigetsu-ji, the Kyotaku denki stories about 'Myō-An'/'Kyorei'

and 'Mukaiji' gave them their respective names.

The term 'Zen' is only to be seen once in the entire Kyotaku denki text:

学心学之

有日、

禅已熟、

曲已就,

"Kakushin studied this; eventually, he mastered in 'Zen', and learned the music well."

Tsuge Gen'ichi's 1977 translation reads like this,

"Gakushin [i.e.: Kakushin, alias Hottō Kokushi] studied the art of the kyotaku.

As the days passed, he went to the heart of Zen philosophy

and attained proficiency in the kyotaku."

NEXT, MORE NECESSARY, CRITICAL QUESTIONS:

Was the Kyotaku denki ever printed and widely distributed to the public anytime before it "surfaced" in Yamamoto Morihide's Kyotaku denki kokujikai, in 1795?

No, not in any form that I know of.

It is a fact, that there is no mention, there are no references, at all,

to the Kyotaku denki text anywhere in all of the many known, preserved documents that were produced by, and written about, the 'Komusō'?

MORE CLARIFICATIONS:

Kyotaku denki and Kyotaku denki kokujikai are not "the same"!

Kyotaku denki, 虚鐸伝記,

is a text composed in the so called 'kanbun',

漢文,

literary style, Chinese writing, while Kyotaku denki kokujikai,

虚鐸伝記国字解,

is a Japanese publication dated 1795, in which the Kyotaku denki is presented in both the original and also "translated"

into then contemporary classical Japanese "mixed script": 'kana-majiri',

仮名混じり,

for easier appreciation.

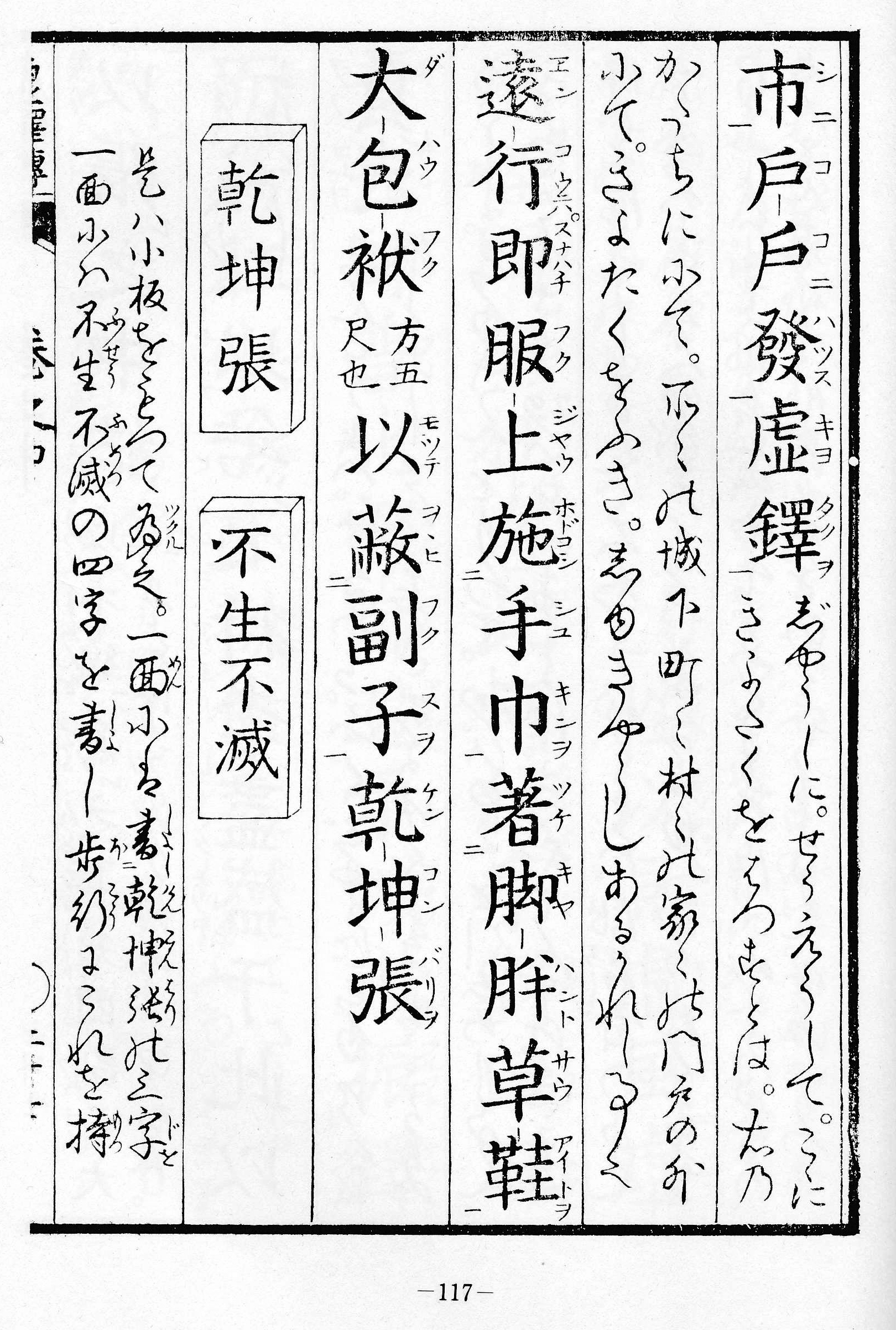

Much of the non-Kanbun text contents is composed in running-hand, cursive style - known as 'sōsho',

x,

and very diffcult to read, even for most of native Japanese readers.

The times and creation of the Kyotaku denki fairy-tale?:

Why - and when - was the Kyotaku denki fabricated historical narrative ever thought out and put into writing?

With the formation in 1640 of the "Bureau of Sects Investigation", 'Shūmon aratame-yaku',

宗門改役,

those numerous unemployed samurai who had previously identified themselves as freely operating, non-attached 'mat monk' begging "followers" of Monk Fuke of China, were suddenly facing a new, harsh reality:

In order to produce convincing evidence and proof that they were not seriously suspicious, secret Christian converts and thus potential traitors in hiding they had to create some religious institution with a proper ideological superstructure and some sort of a pseudo-religious organisation that made them appear as true devotees of the respected, well-established Buddhist faith of Japan.

It was only during the early 1640s that the renowned Rinzai Zen Abbot Isshi Bunshu,

一絲文守, 1608-1646, - in a letter to a hermit monk named Sandō Mugetsu,

addressed as 'Sandō Mugetsu Anjū',

山堂無月庵主, no dates,

- introduced venerated 13th century Shingon & Zen monk Shinchi Kakushin,

the four Buddhist fully invented Buddhist laymen: 'Kyomu yonin',

虚無四人, "Four Kyomu People",

and their twelve likewise fully invented disciples into "Fuke Shakuhachi History".

You can read more about Isshi Bunshu and Sandō Mugetsu here:

1640-1646: Abbot Isshi Bunshu's Letter to a "Proto-komusō" named Sandō Mugetsu

Well now, already in the mid-16th century, the 'mat monks', the 'komosō', are known to have adopted the 9th century Buddhist monk P'u-k'o, a.k.a. Fuke,

as some special kind of an "idol", a "spiritual ancestor" of theirs.

But, on the other hand, there was no heritage, no link whatsoever, back through all those 800 years that had passed since the days of Fuke's alleged lifetime till the mid-1600s,

when the foreign Western missionaries had finally been thrown out of Japan, in 1639 - and the 'komosō' had to become 'komusō'.

Therefore, the "History of the Imitated Bell", the Kyotaku denki, had to be constructed, obviously in order to establish the missing proper,

cultured, and honorable legacy of the new 'Komusō's shakuhachi mendicancy activity - though only supposedly having survived "since times of old":

First of all, we realize that fancy titles of three "sacred" pieces of flute music had to be invented, namely 'Kyorei', 'Kokū', and 'Mukaiji'.

That is to say, we do not know that any of these pieces were in existence before being mentioned in the Kyotaku denki.

Of course, the mid-17th century very first 'komusō' must have favored some kind of shakuhachi music repertory.

But the only few such music titles that we know from Nakamura Sōsan's 1664 writings do not express any "Zennish spiritual overtones", at all.

Now, Fuke Zenji certainly did not play the shakuhachi himself. So, one invented a completely never having existed secular (non-cleric) Chinese family named "Chang",

Jap.: "Chō, 長,

in order to have 'Kyorei', the mythical 'Imitated Bell' tune, transmitted up through the centuries.

16 Family Chang generations of supposed continuous transmission later, allegedly, 'Kyorei' was still alive and well in China in the middle of the 13th century.

Can you believe that?

How then could the 'Kyorei' tune ever reach and spread even further in Japan until this very day today?

Oh, yes: Accidentally so, the renowned Japanese Shingon Buddhist monk Shinchi Kakushin actually happened to be studying Zen Buddhism in China while 'Kyorei',

although only allegedly, still flourished in the Chang family. Kakushin got well acquainted with the Chang descendant, became deeply impressed with the 'Kyorei' piece,

learned to play the music well, and then returned to Japan, in 1254. According to the tale, that is ...

Do remember: That is of course a legend, a myth: Kakushin, later honored with the name Hottō Kokushi, certainly never had anything to do with the shakuhachi in the 13th century.

Kakushin was simply adopted, if not even "taken hostage" you might say, by the mid-17h century 'komusō' in order to establish a sufficiently prominent "Zen Buddhist" link

back to Fuke Zenji himself.

We know from the evidence supplied by the Kaidō honsoku document of 1628 that the 'komosō at that time "boasted" of having as many as 16 branches

of their Fuke-inspired shakuhachi beggar brotherhood. Noteworthily, the names of some of those local 1628 groups certainly re-appear in the names of some

of the sub branches of the later so called "Fuke Sect" of the 'komusō' "organization", like for example 'Yoritake'/'Kichiku', 'Umeji', 'Kinsen', and 'Kaka'.

Of course, those probably quite significant sub groups of early ex-'komosō' 'komusō' had to create their own separate old and honorable heritages,

which is why the Kyotaku denki also introduced the "Four Buddhist Laymen", 'shi-koji',

四居士:

All of them Chinese natives, who - goes the narrative - accompanied Shinchi Kakushin on his ship on his return to Japan in 1254.

Next, according to a couple of separate written later elaborations of the legend, the lines of those four lay Buddhist 'Kyorei' players multiplied by 4 into a total of 16

- that very same number of sub groups that we read about in the Kaidō honsoku of 1628.

So far, so good, you may now think. But: No! The real "coup" embedded in the Kyotaku denki narrative is that of introducing yet another totally made-up, legendary personality,

namely that of the Japanese native named 'Kichiku', 寄竹, the kanji of which can also be pronounced as

'yori-take', meaning "collect bamboo".

The Kyotaku denki describes Kichiku as Kakushin's most gifted and favored student, and as we know that Kichiku was later re-baptized 'Kyochiku'

and made the founder of the Kyōto Myōan Temple, we can nothing but conclude that the Kyotaku denki

was first of all fabricated in order to legitimize and glorify that very important and famous so called 'Komusō' "temple"

in the old Imperial capital Kyōto of Japan.

Publications and one 1977 English translation:

Yamamoto Morihide, compiler and author: Kyotaku denki kokujikai.

Original Kyōto edition published in 1795.

1925 edition publ. by Rakubundō c/o The National Diet Library.

Link: http://dl.ndl.go.jp/info:ndljp/pid/911345

Modern version edited by Kowata Suigetsu,

216 pages, Nihon ongaku-sha, Tokyo, 1981.

National Diet Library bibliographical information, link:

http://iss.ndl.go.jp/books/R100000002-I000001523542-00

Tsuge Gen'ichi: 'The History of the Kyotaku.'

In: Asian Music, Vol. VIII, 2. New York, 1977.

Link to online PDF file:

http://links.jstor.org/sici?sici=0044-9202(1977)8%3A2%3C47%3ATHOTK%3E2.0.CO%3B2-M

OBS: Do note that, most certainly conceived and produced by - and for the benefit of - early 'komusō'

who later created the Kyōto Myōan-ji, the Kyotaku denki text does not mention any "Fuke Sect", Fuke-shū, 普化宗, at all!

Printed with rendering in common classical Japanese in Kyōto in 1795 - see link to an online copy of that publication in the National Diet Library, Tokyo, hewre:

Direct link to a copy of Kyotaku denki at The National Diet Library, Tōkyō

- go to frame 14 and onwards

寄竹 - KICHIKU - or, YORITAKE?

三虚霊譜 - SAN-KYOREI-FU - The Three "Empty Spirit Notations"

It is well known that the legend of the 'Kyotaku', the "imitated bell", has, for long, been regarded as a forgery, or more precisely: A fabrication.

There can no more be any doubt that the text was primarily produced for the benefit and strengthened reputation of the Kyōto 'komusō'

and the somewhat later founded Myōan Temple in SE Kyōto.

The monk Ton'o, the alleged author of the text, is however reported to have been active during the late Kan'ei period (1624-1644),

and judging from the subject matter of the story, it could although but only theoretically, have been composed already at that time.

It is, in any case, noteworthy, that central elements of the story about Hottō Kokushi, the four devoted men and Kyochiku

(formerly Kichiku, in the Kyotaku denki) were in fact in existence at least in 1735, contained in the Myōan-ji document

Kyorei-zan engi narabi-ni sankyorei-fu ben, see below.

- - -

学心学之有日、禅已熟、曲已就、

而告別干張参辞舒州、

而解纜干明州、南宋理宗宝帝祐二年、帰船干本邦。

"Gakushin [i.e.: Kakushin, alias Hottō Kokushi] studied the art of the kyotaku. As the days passed, he went to the heart of Zen philosophy

and attained proficiency in the kyotaku;

finally he took leave of San [Kakushin's alleged kyotaku teacher Chōsan] (to return to Japan).

Gakushin left Hsü-Chow for Ming-Chow, where he unmoored his ship.

It was in the second year of the Sung Dynasty that he returned to Japan, where it was the sixth year of Kenchō,

in the the reign of Emperor Gofukakasu."

自是学心、或高野山入、或出洛陽城、

逍遊有年、造立一寺干紀州、号西方寺、

而終住干此。

"Thereafter, Gakushin confined himself in a mountain temple at Kōyasan, sometimes visiting the capital (Kyoto).

Years passed, and he founded a Buddhist temple named Saihōji in the province of Kishū [present-day Kōkoku-ji in Wakayama Pref.],

where he established his permanent abode.

- - -

徒中有寄竹者、以禅心殊切、敬師益甚、

学心亦親眤之異干他弟子、

一時学心告之、

"Among his numerous students, there was one called Kichiku. The more earnest he became in his devotion to Zen Buddhism,

the more ardent was his admiration for his master.

Gakushin also took a more kindly interest in him than in other students.

One day Gakushin told Kichiku:"

以在宋之時伝 得虚鐸音今尚能調之、

且謂、欲長授干汝面嗣此之伝、

寄竹踊躍拝謝、伝此之音、熟習嗜寿日不置。

"'When I was (studying) in the country of Sung, I was instructed in the kyotaku and I perform on it well even today.

I would like to initiate you in this flute in the hope that, as my successor, you will pass this art on to posterity.'

Kichiku, dancing for joy and expressing his gratitude, received instruction in this music and attained proficiency in the instrument.

He took delight in playing it everyday untiringly."

他弟子、国作、理正、法普、宗恕、

四人亦能学此管、世称四居士。

"There were four more students - - Kokusaku, Risei, Hōfu and Sōjo - - who also learned this flute well.

They were known to the world under the (collective) title Shikoji ("Four Devoted Men")."

- - -

Quoted from the Kyotaku denki, trsl. by Tsuge Gen'ichi, 1977.

Printed in Asian Music, Vol. VIII, 2. New York, 1977.

The complete translation is available at:

www.links.jstor.org

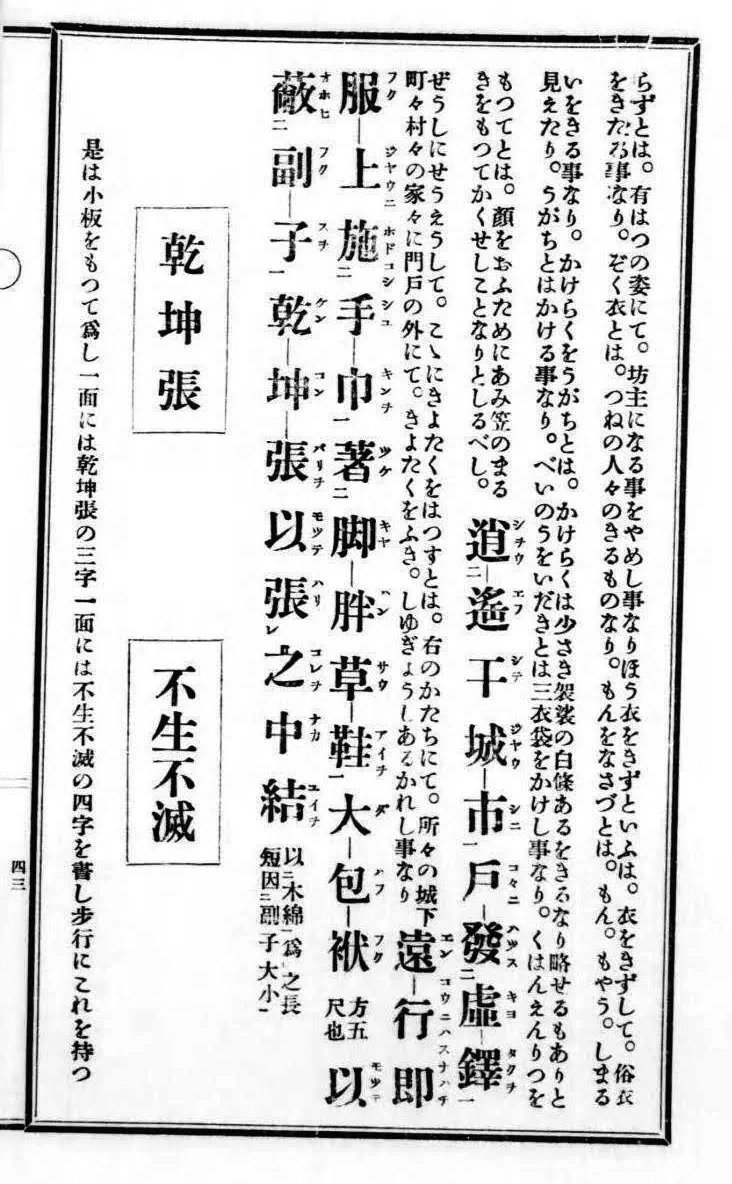

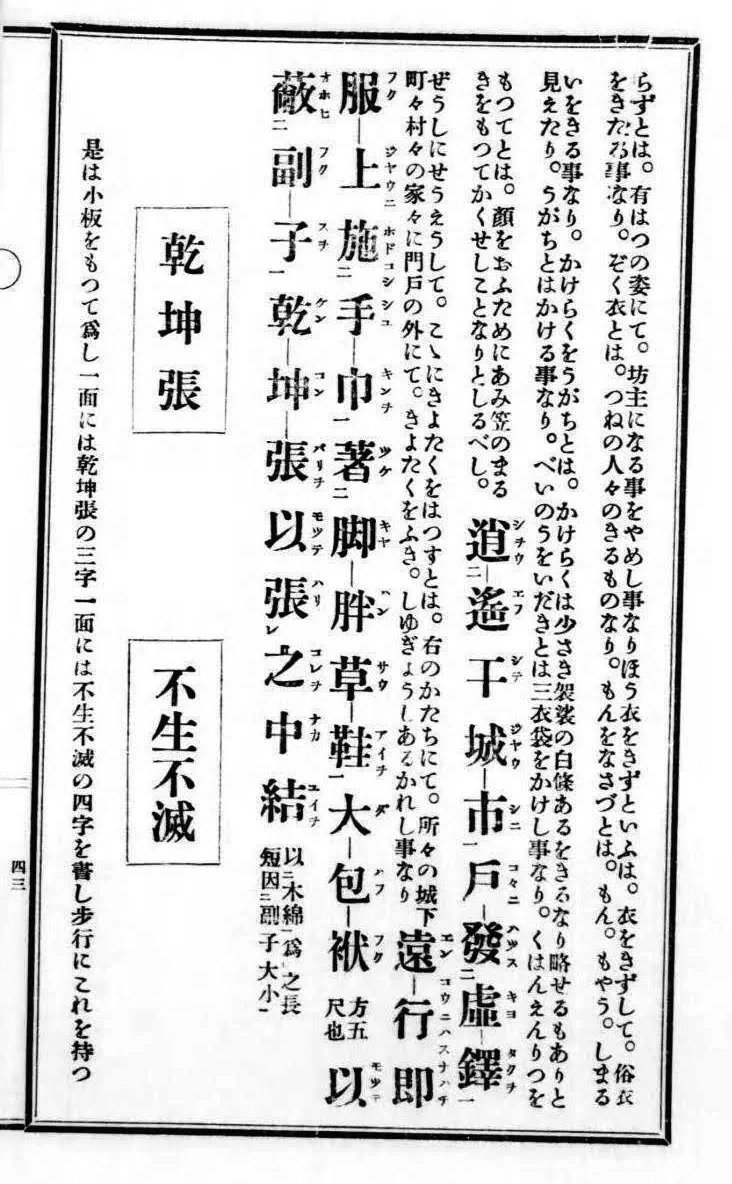

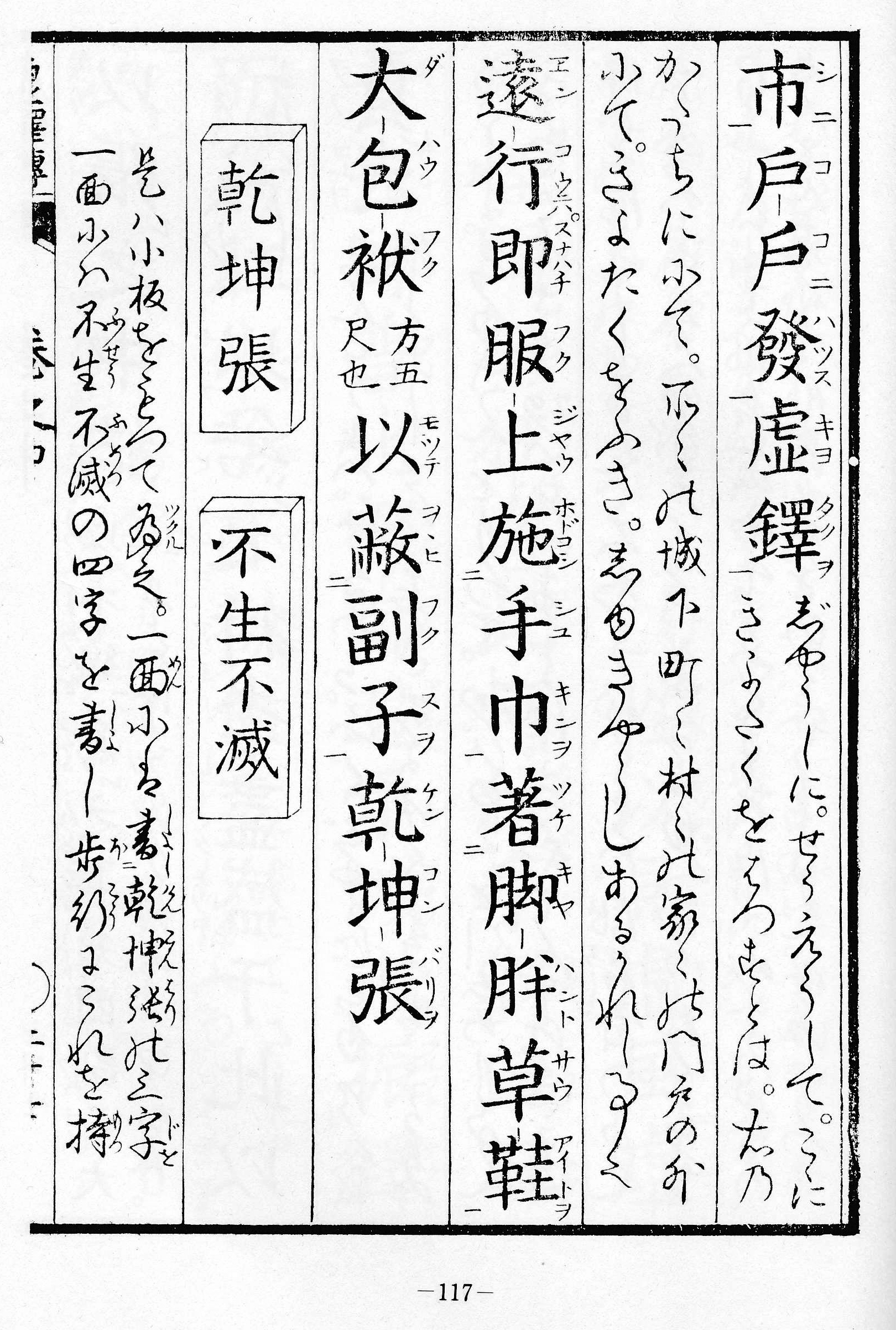

乾坤張 - KEN-KON-BARI

不生不滅 - FU-SHŌ FU-METSU

小坂以為之、一面書乾坤張三字、

一面書不生不滅四字。

"On one side of a small wooden board three characters are written: "heaven-earth-fashion" ['ken-kon-bari'];

on the other side is written: "non-born non-perished" ['fu-shō fu-metsu']."

From the 'Kyotaku denki kokujikai', the editor Yamamoto Morihide's comments. Trsl. by Torsten Olafsson.

The concept of 'fu-shō fumetsu' is most central in Mahayana Buddhist thought and appears in most, if not all,

of the Mahayana sutras, including the Heart Sutra [Hannyashin-gyō

般若心経, skt. Prajnapāramitā Hrdaya], the best known and most popular of all Buddhist texts.

The essence of 'fu-shō fumetsu' is also being expressed as 'mu-shō mu-metsu',

無生無滅.

Link: https://note.com/kataha_comjo/n/n2de541ae90c1

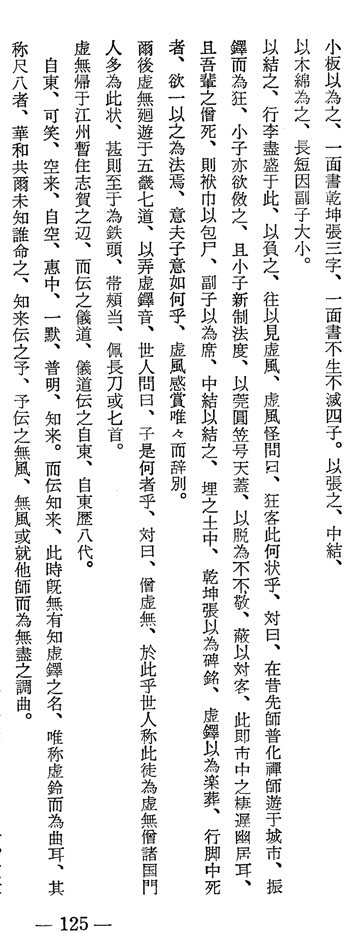

Kyotaku denki, original text in kanbun. Source: Nakatsuka 1979, pp. 123-125.

|

|