「修行尺八」歴史的証拠の研究 ホームページ

'Shugyō Shakuhachi' rekishi-teki shōko no kenkyū hōmupēji - zen-shakuhachi.dk

The "Ascetic Shakuhachi" Historical Evidence Research Web Pages

Introduction & Guide to the Documentation & Critical Study of Ascetic, Non-Dualistic Shakuhachi Culture, East & West:

Historical Chronology, Philology, Etymology, Vocabulary, Terminology, Concepts, Ideology, Iconology & Practices

By Torsten Mukuteki Olafsson •

トーステン

無穴笛

オーラフソン •

デンマーク • Denmark

|

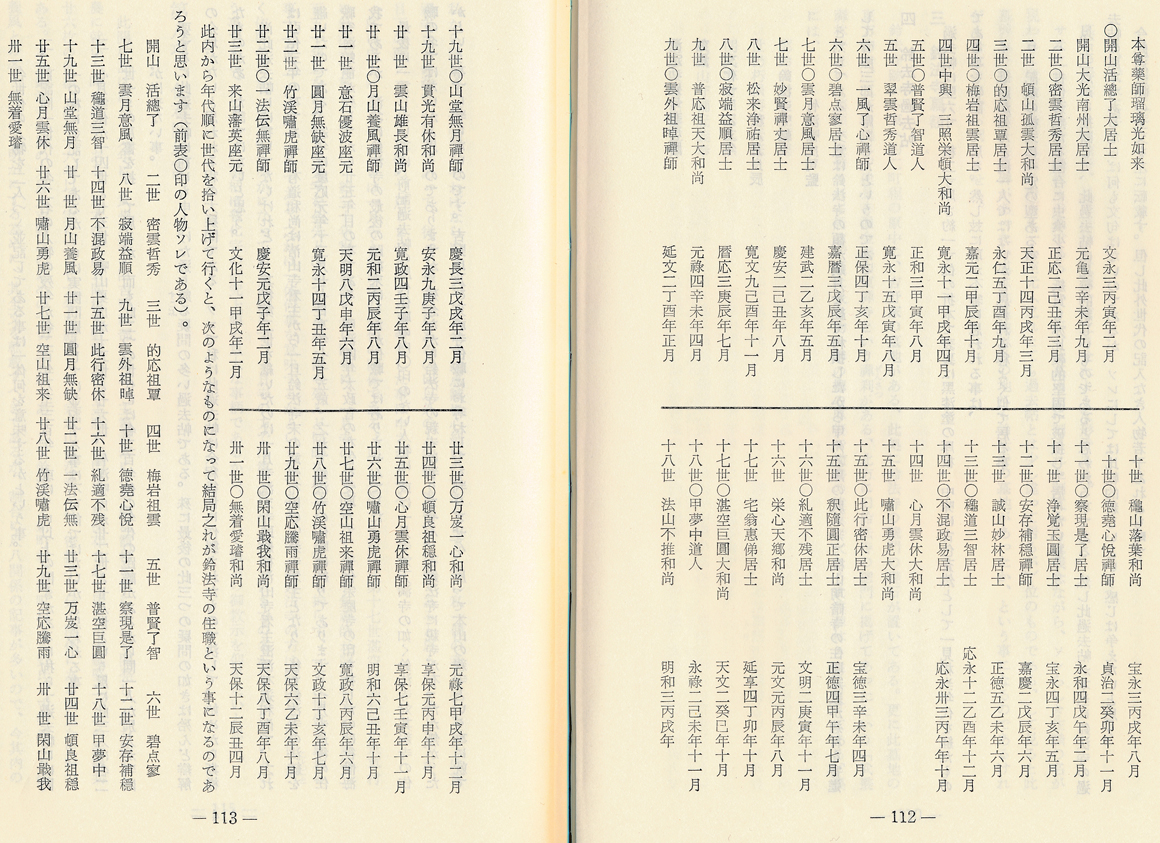

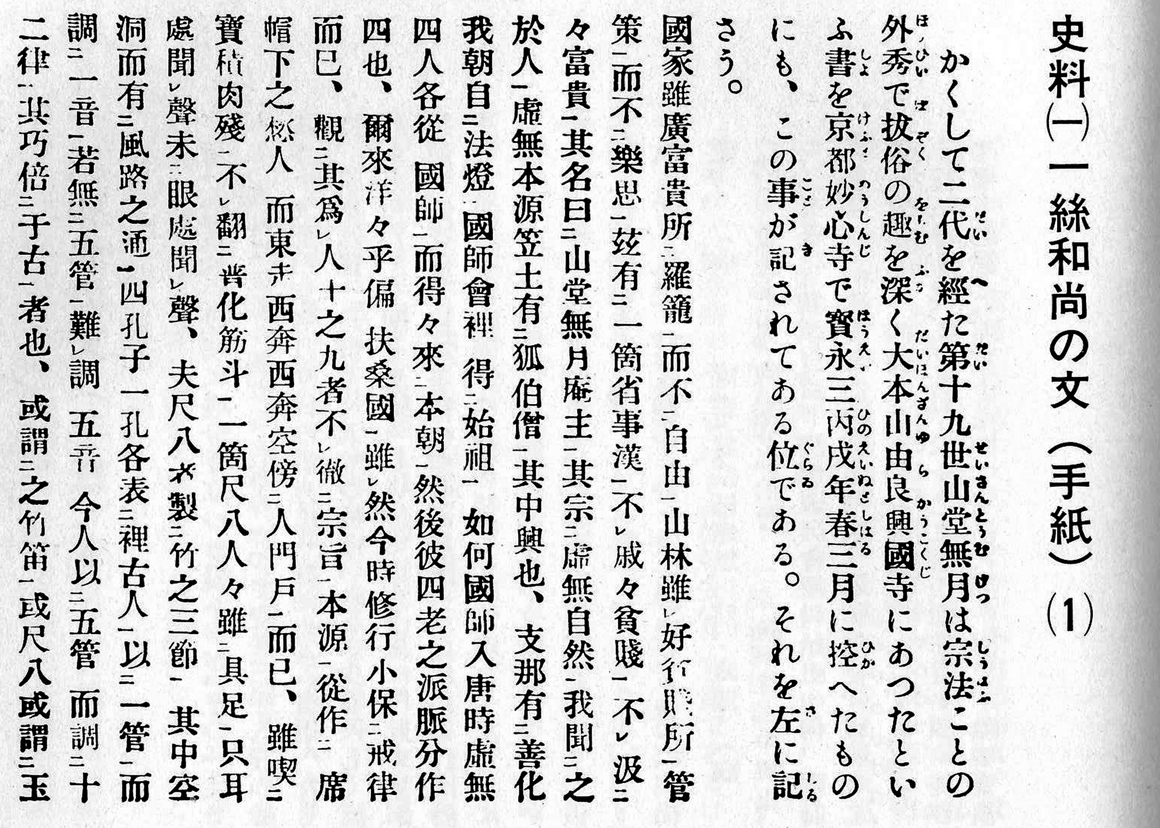

1640-1646: Abbot Isshi Bunshu's Letter to

示虚無僧為山堂無月庵主 |

|

|

View a full reproduction of Abbot Isshi's Letter to the komusō Sandō Mugetsu as PDF file: 1 MB |

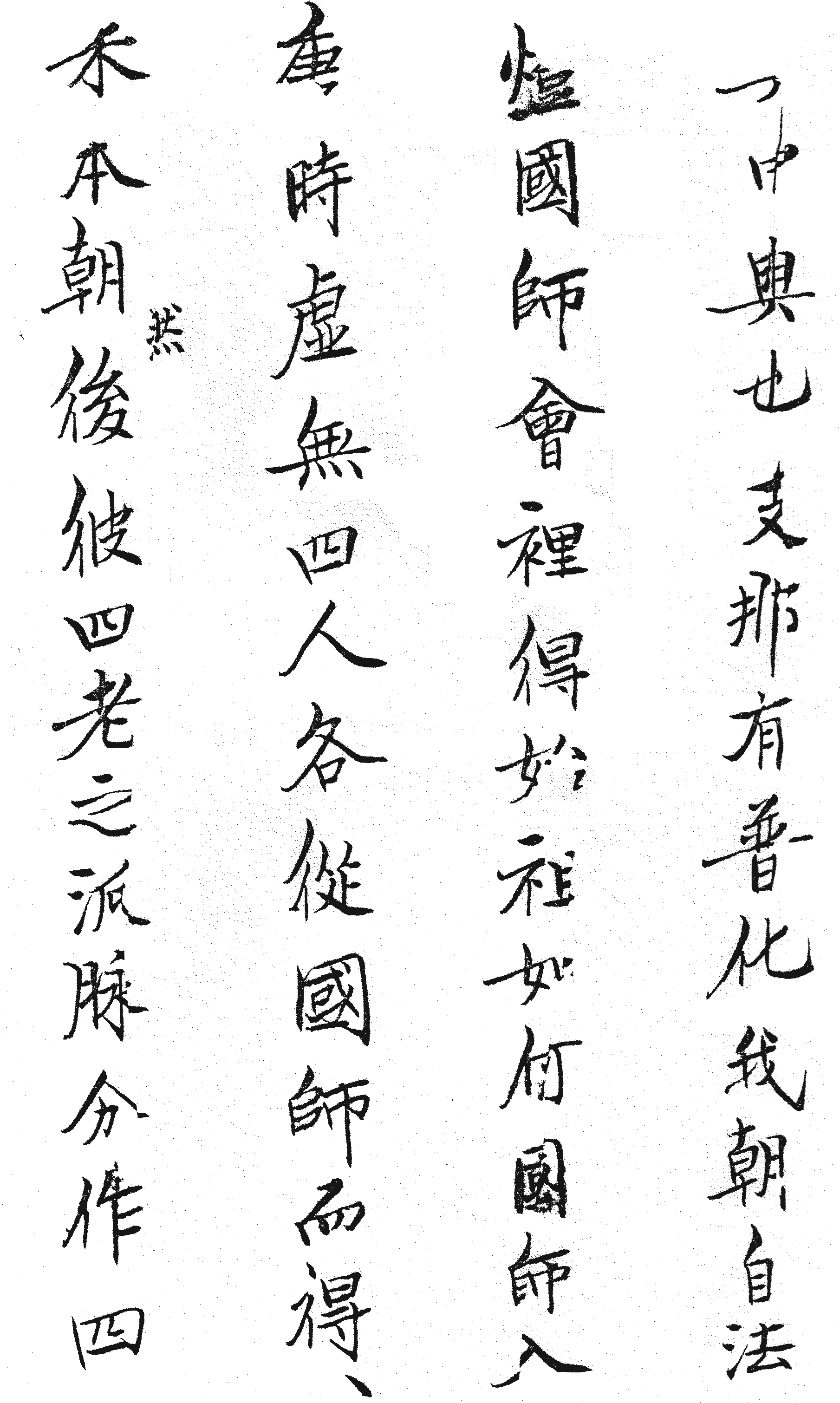

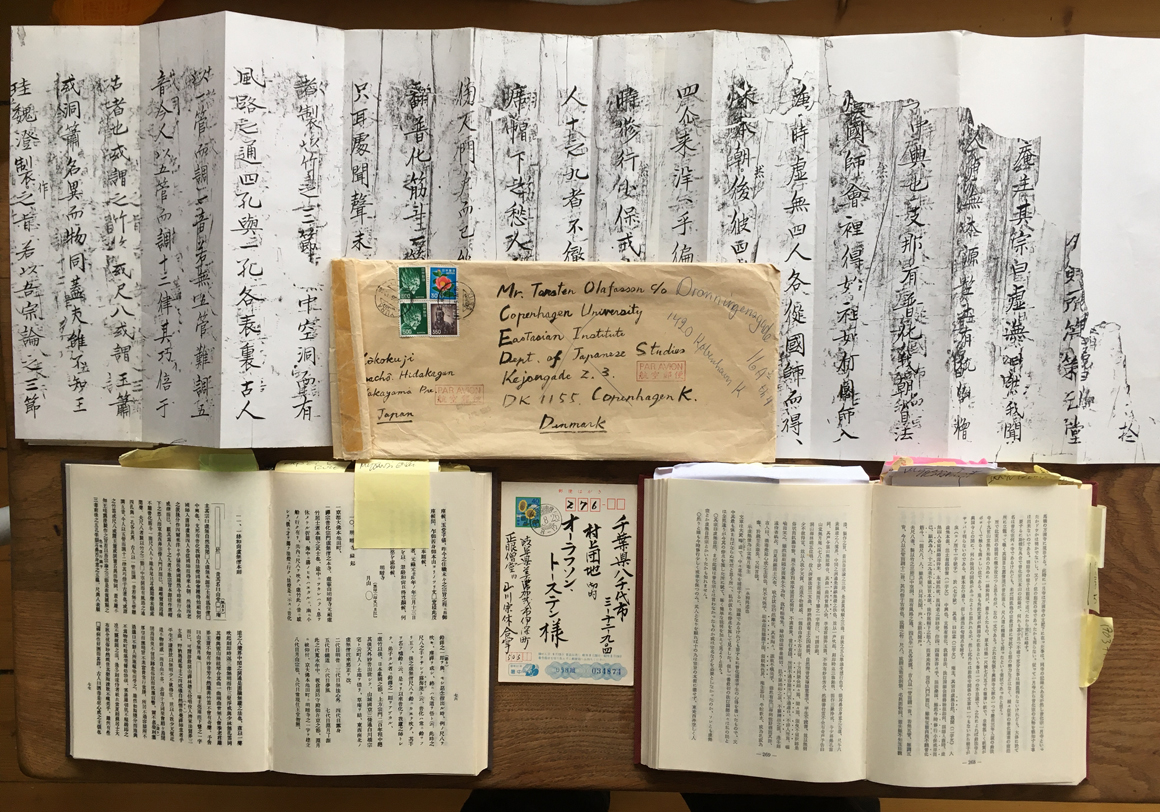

Here you see the opening section of my xerox copy of the original letter from Isshi Bunshu to the 'komusō' Sandō Mugetsu that was made and sent to me by Yamakawa Sōkyū, 山川宗休,

of the Kōkoku-ji in Yura, Wakayama Pref., in early 1985.

In the picture you also see Isshi's letter as reprinted in Mori, 1981 (1st edition 1938),

and Nakatsuka, 1979 - two absolutely essential literary sources

of ascetic shakuhachi history and ideology.

Left: The Kōkoku-ji 'Sho-in' library building. Source: Google Maps, photo by KY SG.

Right: The Kōkoku-ji Main Hall. Source: Wakayama TV website

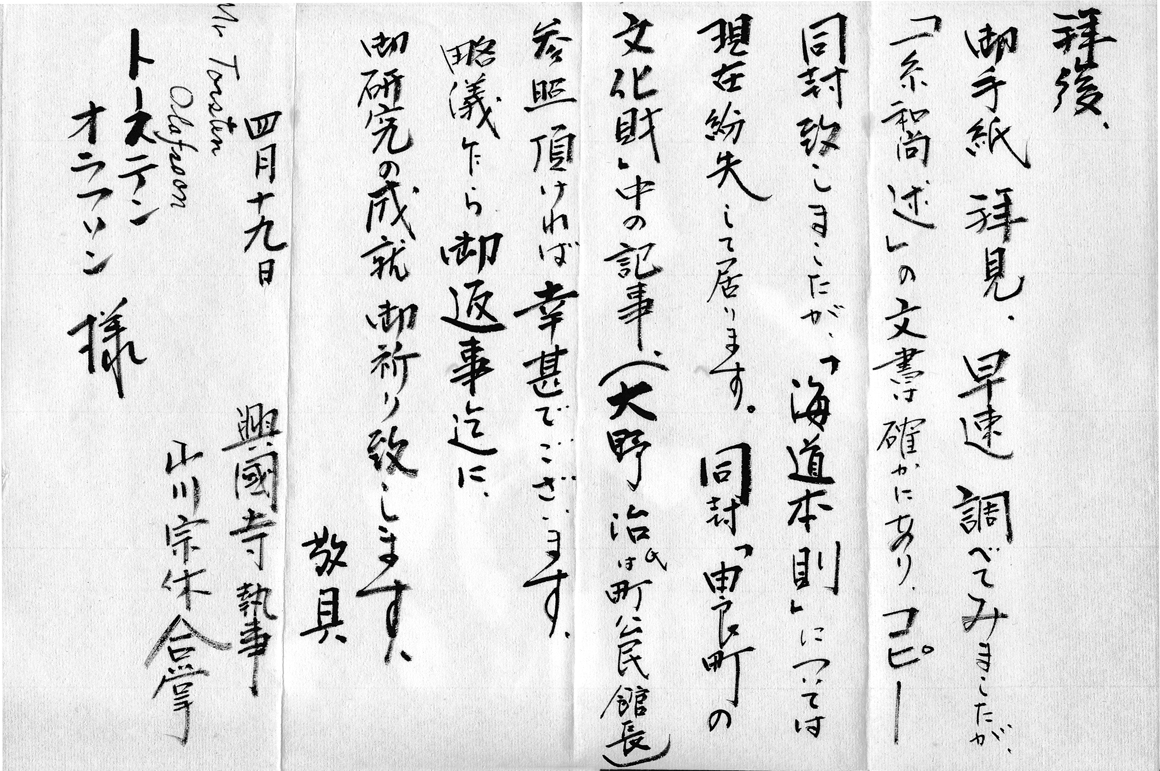

Scanning of the Kōkoku-ji head librarian Yamakawa Sōkyū's

April 19, 1985, letter to Torsten Olafsson.

In this letter Mr. Yamakawa explains that while he can enclose a complete xerox copy

of Isshi Bunshu's letter (cols. 3-4 from the right),

the 'Kaidō honsoku' document "has now gone missing": 'genzai funshitsu shite orimasu,'

現在紛失して居ります (cols. 4-5).

As with the Kaidō honsoku of 1628, Abbot Isshi's Letter to the komusō Sandō Mugetsu represents an equally important and very unique source of mid-17th century very early Komusō Shakuhachi ideology only in the making.

Here follows (an attempt at) a preliminary English translation of the document, almost complete, as of Spring, 2013 (the paragraphing is mine).

Trust me: This text is definitely a major challenge, both to the linguist, the musicologist, the student of philosophy, and to the historian!

Notes to the presentation of the Japanese text:

【?】 = missing or illegible kanji in the original manuscript.

【kanji】 = probable character inserted where a kanji is missing or illegible in the original manuscript.

(kanji) = notes added/inserted in the original manuscript in different writing style/hand.

* following a kanji = the preceding kanji was written with a non-standard or old version of the ideograph in the original manuscript by Isshi Bunshu.

Par. 1

【??????????? - 11 kanji missing】

... 於 ...

【?????? - 6 kanji missing】

... 貴、

- Opening paragraph – Worm-eaten - upper right corner of the scroll damaged by insects.

11 kanji missing.

1 kanji: “… at …” [Jap.: ni oite].

6 kanji missing.

1 kanji: ”… honor(able) …”[Jap.: ki].

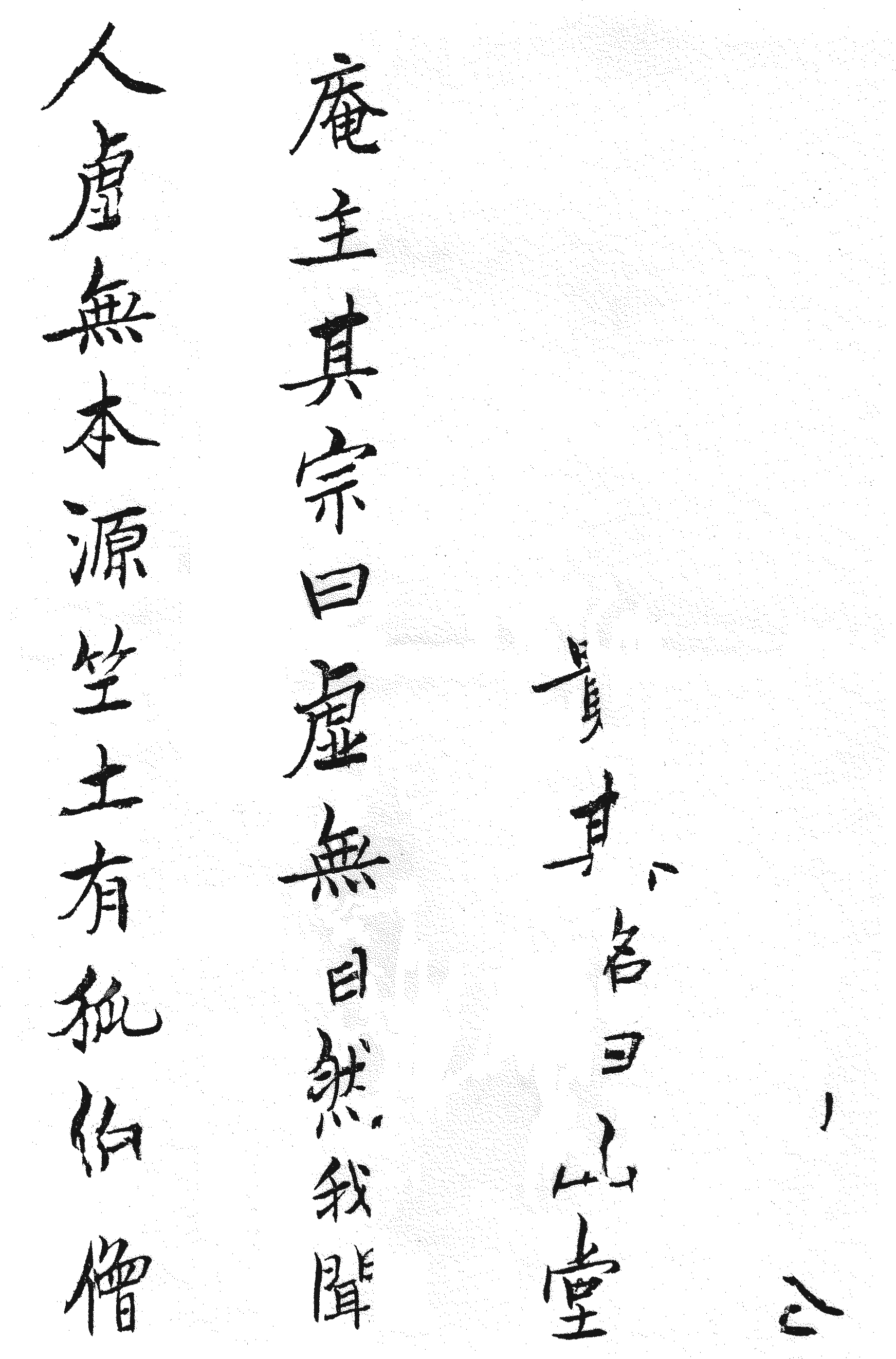

Par. 2:

其名曰『山堂【無月】庵主』、

”[As for] That [personal] name, [he] is called Sandō Mugetsu, the hermit.”

Par. 3:

其宗曰『虚無自然』、

”[As for] That sect, [it] is called “K(y)omu Nature” [Jap.: K(y)omu Shizen].”

Par. 4:

我聞

【?? - 1 or 2 kanji missing】

人虚無本源、

“I have inquired with a [1 kanji missing: ‘learned’?] person regarding the origin of [the]‘K(y)omu’.”

Par. 5:

竺土有狐伯僧*

【? - 1 kanji missing】

中興也、

“[I learned that:] In India there was a clever, old monk [1 kanji missing: ‘who was the’?] founder.”

Par. 6:

支那有普化、我朝自, 法燈國師會裡得始祖如何、

“In China there was Fuke; [as for] my [own] country itself, how possibly could Hottō Kokushi accomplish as the originator of the congregation?”

Par. 7:

國師入唐時,虚無四人各従國師而得々來本朝,

“When Kokushi was in China, one after the other four K(y)omu persons joined him and, succesfully, came [back with Kokushi] to this country.”

Par. 8:

(然)後彼四老之派脉分、作四爾來洋々乎、偏扶桑國、

“Later, the paths [lit.: 'branch veins'] of these honorary men separated into four, respectively [thus totalling 16], and - travelling in all directions - wherever they came they brought relief to the Buddhist community."

Par. 9:

雖*然今時修行小保戒律而己、

“However, the ascetic practice [Jap.: shugyō] in present times is only poorly [lit.: ‘little’] observing the commandments; and that is so indeed.”

Par. 10:

顧其為人,十之九者不徹宗旨*本源、

“When I examine those persons who are practicing [as k(y)omu], nine out of ten [of them] do not understand the original essence [lit.: ‘source’] of the sect’s instructions.”

Par. 11:

徒作席帽下之愁人、

“[Their] Lack of devotion makes [them into] but miserable persons underneath basket hats.”

Par. 12:

而東走西奔、空彷*人門戸而己、

“And so, hurrying in the East and hastening in the West, they simply wander absentmindedly [or, ‘in vain’] around people’s gates; and that is so indeed!

Par. 13:

雖*喫寶積肉*残不翻普化筋斗、

“Even though they ate the earthly remains of [Banzan] Hōshaku, they would certainly never change into the muscles [i.e.: the ‘logic’] of Fuke!”

Par. 14:

一箇尺八人々、雖*具足、只耳處聞聲、未眼處聞聲*、

“[As for] Persons with one shakuhachi, although [they are] equipped [with it], it is the ear that manages hearing - not the eye that manages hearing.”

Par. 15:

夫尺八者、製以竹之三節

【? - 1 kanji missing】

中空洞、

而有風路之通、四孔與一孔各々表裏、

“The shakuhachi is made from a piece of bamboo with 3 joints [or, ‘nodes ‘, Jap.: mi-bushi] with a hollow cavity [cut out] inside of it.

Then, when the airstream can pass through [it], four and one holes [are drilled] on the front and back [respectively].”

Par. 16:

古人以一管而調一音、

若無五管、難調五音、

今人以五管而調十二律、

其巧倍于古者也、

“The ancients [lit.: ‘old people’] used a single pipe and produced [lit.: ‘intoned’] a single sound.

If there were not 5 pipes, it was difficult [i.e.: ‘impossible’] to intone [or, ‘tune’] the five notes.

Today’s people [lit.: present-day people] use 5 pipes and tune [the] 12 steps [or, ‘pitches’, i.e. the 12 semitones of the octave].”

“That expertise originated with the ancients.”

Par. 17:

或*謂之竹笛、 或*尺八、或*謂玉簫、或*洞簫、

“Some oral traditions [call it] chiku-teki [alt.: take-bue - i.e.: ‘bamboo flute’]; some [call it] shakuhachi.

Some oral traditions [call it] gyoku-shō [i.e.: ‘jade flute’]; some [call it] dōshō [Chin.: t’ung-hsiao].

The names differ, [but] it is the same thing.”

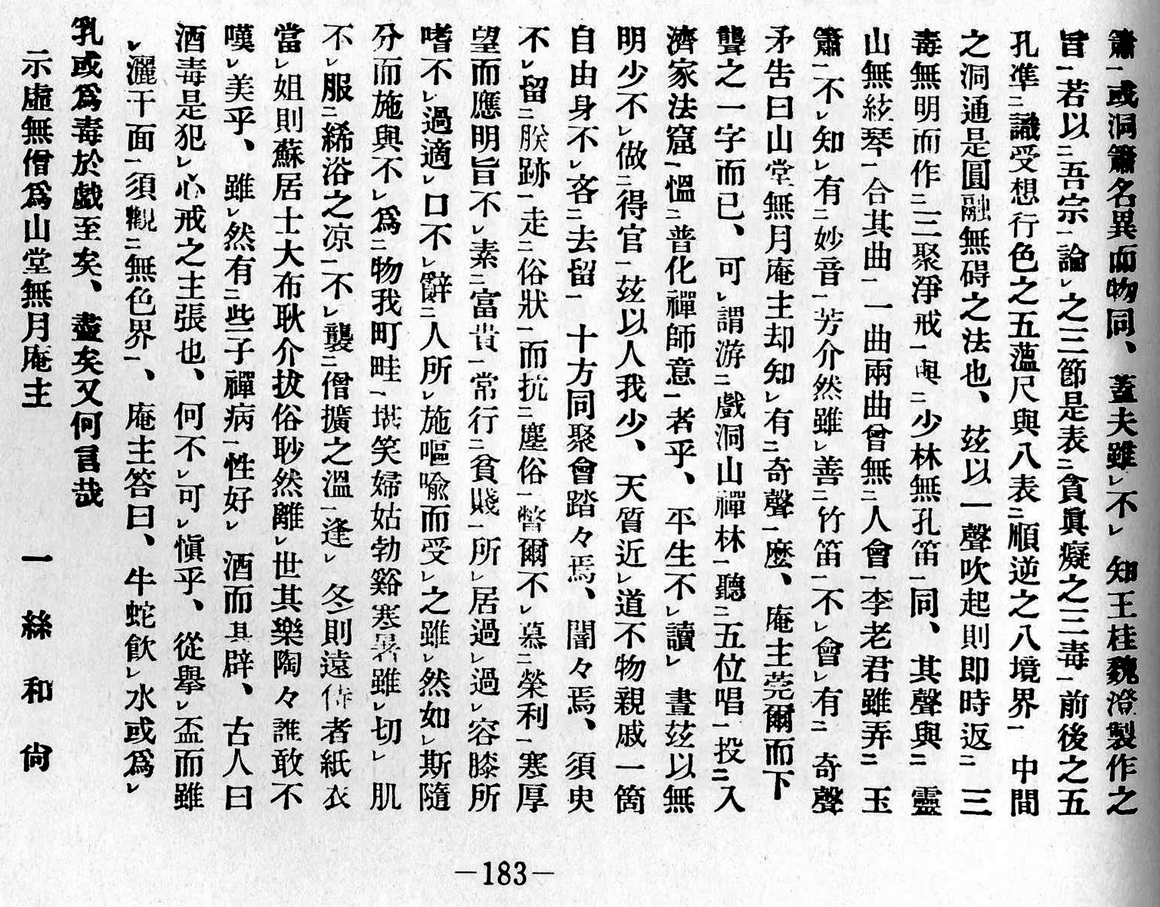

Par. 18:

蓋夫雖*不知玉*珪魏澄、製(作)之旨*、

若以吾宗論之三節、是*表貪*嗔*癡*、

After all, if one does not understand [or, ‘grasp’] the ‘Lofty Clarity of the Jade Tablet’ [or, ‘sceptre’ – Jap.: gyokkei gichō], and the principles of [shakuhachi?] manufacture, and do not observe [lit.: ‘employs’] the Three Fundamental Tenets [lit.: ‘three joints’ - Jap.: mi-bushi] of our school’s teaching [i.e.: that of Zen Buddhism] - that expresses the Three Poisons [or, ‘malices’] of Greed, Anger, and Ignorance.”

Par. 19:

前後之五孔準眼耳鼻舌身意之五蘊*/薀*、

(Note added to the original manuscript in a different writing style:

識受想行色*乎)

”The five holes on the front and the back [respectively] [are] the collected [powers of] Eyes [or, ‘seeing’], Ears [or, ‘hearing’], Nose [or, ‘smelling’], Tongue [or, ‘tasting’], and Body-Mind.”

[In the original manuscript an explanatory note has been added, in different writing:

“Discrimination between receiving ideas and perceiving colours?”]

Par. 20:

尺與八表順逆之八境界、

中間之洞通、是*圓融無礙之法也、

“Shaku and Hachi expresses [or, ‘represents] the ‘right and wrong’ of the Eight Environments [determined by Karma].

[As for] the hollow passage way of the interior space, that is the Doctrine of Non-obstructed Universality [Jap.: enyō muge/mugai].”

Par. 21:

茲以一聲*吹起、則即時返三毒之無明、而作三聚*之淨戒、

“Blowing forth increasingly with one voice, that [then] immediately eliminates the Muddiness of the Three Poisons [Jap.: sandoku no mumyō] and manifests [lit.: ‘makes’] the Precepts of the Three Buddhist Assemblies [Jap.: sanshū no jōkai].”

Par. 22:

與少林無孔笛同、其聲*與霊山無絃琴合、

其曲一曲兩曾無人會、

李老君雖*弄玉簫、不知有妙音芳*介、

然雖*善竹笛不會有奇聲*、

“Likewise, this is the same as the ‘Shōrin Flute Without Holes’ [Jap.: Shōrin mu-ku-teki].

Its sound [lit.: ‘voice’] equals that of Ling-shan’s [Jap.: Reizan, 1225-1325] ch’in with no strings [Jap.: kin, the class. Chinese zither] - that music of all music no one ever encountered.

Even though Master Li-lao [Jap.: Rirō, no dates] excelled with his jade flute, he did not know that there existed [such a] fragrant medium [?] of mysterious sound [Jap.: myōon hōkai].

However, a ‘good’ bamboo flute does not necessarily produce an austere sound.”

Par. 23:

予告曰、山堂無月庵【主】

【6-7 kanji missing】, 庵主莞爾、而下籠聾【之一字而】己、

可謂游*戲*、

“As I noted, saying before, hermit Sandō Mugetsu [6-7 kanji missing] - - - ,

You [lit.: ‘the hermit’] smile, and the lower part of the character for ‘deafness’ [is the character for ‘ear’?]; and that so indeed!

I [just] cannot help joking … [lit.: ‘I must say a joke’].”

Par. 24:

洞山禅林聴五位唱、投*入済家法窟弄三玄曲、

“Priest Tung-shan [Jap.: Dōsan, 807-869, a Sōtō Zen monk] heard the recital of the ‘Five Ranks’ [Jap.: go-i];

he put together and established the family code [Jap.: ka-hō], explored and trifled with the Three Occult Music Pieces [Jap.: sangen (no) kyoku].”

[T.O.: go-i is very important in Sōtō Zen thought. Zengaku Jiten p. 345.]

Par. 25:

野衲熟視庵主之四威儀自然慴普覺禅師意者乎、

平生不讀書、茲以無明少不做得管、

“I doubt that the purity of the mountain dwelling hermit Jukushi’s [?, no dates] Four Dignified Manners [Jap.: i-gi] threatens the idolizers of Fu[ke] and Kaku[shin]?

[T.O.: i-gi is very important in Sōtō Zen thought. Zengaku Jiten p. 20: Practicing/walking, living, sitting, sleeping/lying.]

Usually, they do not read books, and here, because of their ignorance, they are not at all capable of performing administration.”

Par. 26:

茲以人我少天質、近道不物親戚、

一箇自由身不吝去留、

十方同聚会蹈々焉問*問*焉、

“Here, because of Human Selfishness there is little Divine Talent, and following short cuts does not bring about empathy [or, ‘compassion’? - lit.: ‘being intimate with sadness’].

The Liberated Body [or, ‘person’] moves and rests with no restraint [lit.: ‘not unwillingly’].

How can it be, then, that they gather everywhere in crowds and engage in quarrels and fights?”

Par. 27:

須曳、不留朕跡、

是俗状*而抗塵容瞥、

爾不慕栄利、寒厚望、而応明旨*,

“Do not in any way obstruct the Authority of the Imperial Court [lit.: ‘the Precedence of the Imperial We’].

That corrupts the state of the world, and … [4 kanji awaiting a satisfying translation].

Thus, do not adore Honor and Profit, be cold towards Shameless Desire, and be in agreement with the Self-evident Principles.”

Par. 28:

不素富貴、常行貧*賎*、

所居不過容膝、所【居】不過適口、

不辞*人所施、嘔喩*而受之、

然雖*如斯随分、而施與不為物、

“Do not accumulate Wealth and Honor; do always practice Poverty and Lowliness.

Being at places, do not overdo resting your knees.

Being at places, do not exceed [with regard to] satisfying your mouth [i.e.: in terms of eating and drinking].

Do not refuse a human resting place offered as alms – accept [lit.: ‘receive’] it (‘with no repulsive word’?)

[T.O.: Here 2 specific kanji are somehow difficult to translate satisfyingly.]

Even though it is as such, exceedingly, almsgiving represents something disadvantegous.”

[T.O.: The exact meaning of this last sentence is somewhat unclear.]

Par. 29:

我町畦堪笑、

婦姑勃石*、

寒暑、雖*切*肌、不服糸*糸*之涼、

不襲繪糸*之温、

“Our towns and fields are in full bloom [lit.: ‘are equal to smile’, i.e.: ‘are equal to prosperity’].

Wives and mothers-in-law engage in quarrels [lit.: ‘work hard on stones’].

[Be it] cold or hot, even though they cut their skin, they are not devoted to the coolness of hempen [summer] kimonos – they do not esteem the slight warmth of embroidered silken.”

[T.O.: This paragraph certainly presents a challenge to the imaginative translator … ]

Par. 30:

逢冬則遠侍者、

當夏則蘇居士大布、

“The coming of winter accords with the Paper Garments of remote attendants.

The advent of summer accords with the renewal of the Buddhist layman’s Large Cloth [Jap.: ō-fu].”

Par. 31:

耿介拔俗、耿*然離世、

其楽陶*【々】、誰敢不嘆美乎、

[8+10 kanji - awaiting final and satisfying translation – the subject matter is, however, not specifically shakuhachi-related.]

Par. 32:

然雖*有些

【1 kanji missing: 少?】 禅病性好酒、

而其辟古人曰、

『酒毒是犯心戒之主張也』、 何不可慎*乎、

”There is, however, to some extent [lit.: ‘a little’] a Zen addiction [lit.: ‘disease nature’] to being fond of alcoholic liquor [Jap.: sake, i.e.: ‘rice wine’]. And, [as for] that misdeed the ancients said,

‘Alcoholic poison [i.e.: ‘getting drunk’], that sins against the emphasis on the essential commandments for the Mind [Jap.: kokoro/shin].’

For what reason should one not be moderate ... ?”

Par. 33:

縦擧*盃、而雖*灑于面*、

須観無色界、

“Even if one celebrates a congratulatory cup [i.e. f.i.: ‘a toast’], although you pour it full, then:

By all means, one shall envision [lit.: ‘see’] the Realm of No Colors [Jap.: mu-shiki kai].”

[T.O.: The representative colour of the supreme Shingon Buddha Dainichi Nyorai, Skt.: Vairocana, is that of the colour white which is colourless, yet possessing all colours of the spectrum.]

Par. 34:

庵主答曰、

『牛蛇飲水、或為*乳、或為*毒』、

“The hermit [Jap.: anju] replies, saying:

‘The oxen thirstily drinks water – sometimes it turns into milk, at times it becomes poison.”

Par. 35:

於戲至矣盡矣、又*何言哉、

“Leading up - and concluding - with a joke! Again: What do You say?”

Par. 36:

示虚無僧*為*山堂無月庵主、

一絲和尚述也。

“Addressed to the hermit Sandō Mugetsu, who has become [or, ‘is’] a Komusō.

“Stated by Isshi Oshō.”

Translation by Torsten Olafsson, Denmark

Digitized version of Abbot Isshi's Letter

The study of old, original Japanese manuscripts does indeed represent a special challenge:

Japanese authors of bygone days often expressed themselves in quite archaic language and frequently used 'non-standard' ideographs (kanji) in their writings.

The actual meaning of such texts often appear to be quite obscure to present-day Japanese scholars and - so much more - to non-Japanese students of the language.

Hopefully, the transcription presented here may be helpful in the further study of the document:

|

|

Abbot Isshi's Letter to Sandō Mugetsu digitized, presented as PDF file: 320 kb |

By the way, in the appendix of Kowata Suigetsu's 1981 edition of Yamamoto Morihide's 1795 Kyotaku denki kokujikai you find a very interesting alternative version of Isshi Bunshu's letter:

Kowata Suigetsu's 1981 alternative version of Isshi's Bunshu's 1646 Letter, bottom.

Reference:

Kowata Suigetsu, compiler & editor: Kyotaku denki kokujikai.

By Yamamoto Morihide, Kyōto, 1795.

216 pages, Nihon ongaku-sha, Tokyo, 1981.

| To the front page | To the top |

"To the hermit Sandō Mugetsu"