「修行尺八」歴史的証拠の研究 ホームページ

'Shugyō Shakuhachi' rekishi-teki shōko no kenkyū hōmupēji - zen-shakuhachi.dk

The "Ascetic Shakuhachi" Historical Evidence Research Web Pages

Introduction & Guide to the Documentation & Critical Study of Ascetic, Non-Dualistic Shakuhachi Culture, East & West:

Historical Chronology, Philology, Etymology, Vocabulary, Terminology, Concepts, Ideology, Iconology & Practices

By Torsten Mukuteki Olafsson •

トーステン

無穴笛

オーラフソン •

デンマーク • Denmark

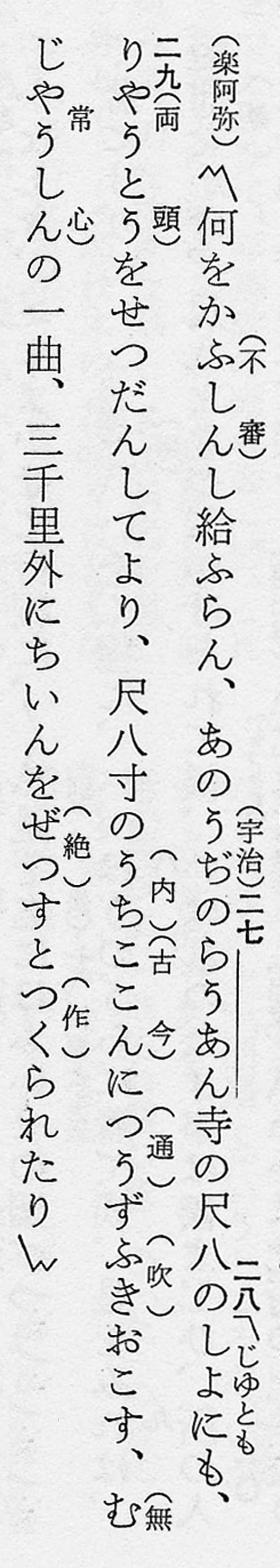

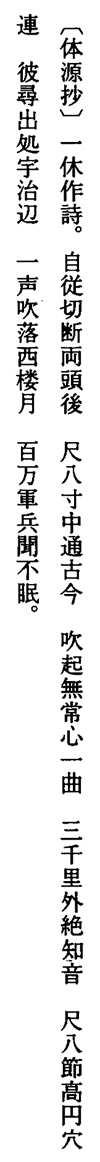

Figure 6 Ikkyū's (???) "Ryōtō poem" in the Taigenshō, 1512 At least acc. to Ueno Katami 1983 edition  Figure 8 Ikkyū's "Uji poem" in the Taigenshō, 1512 Ueno Katami 1983 edition |

Late 15th Century?: The Kyōgen Play 'Rakuami'

楽阿弥

|

|

|

See the complete text of 'Rakuami' as printed in the Kyōgen-ki, 1917 edition. The Royal Library, Copenhagen, Denmark (PDF, 3,1 MB). |

COMMENTARY

13: "The tenor flute; the alto flute; the soprano flute, the double flute ... " - the actual flute types mentioned are:

Ō-shakuhachi, ko-shakuhachi, shi-teki, han-teki and ryū-teki, i.e.: "all kinds of flutes" (cp. figure 1, to the left).

Some might perhaps speculate whether the "big" shakuhachi,

ō-shakuhachi, could have been not just a longer, but also a thicker and more heavy

type of vertically held flute than the "small" shakuhachi, ko-shakuhachi, which would then have been shorter, and thinner - like the "hitoyogiri" ... ?

However, the overall meaning may rather be that of "shakuhachi in various sizes".

16: "The Temple of Ryoanji" - the correct romanization of the ideographs should be Rōan-ji (cp. figure 2, to the left).

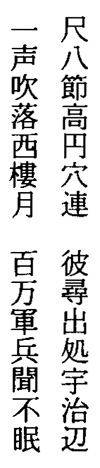

16 - the poem, in Sadler's quite confusing, miscomprehended translation:

"When the two extremities of the bamboo are cut and determined,

between the eighteen inches of its length a whole world lies.

And in one melody that breathes the spirit of impermanence

there lies a power of communication

that transcends the confines of the Empire."

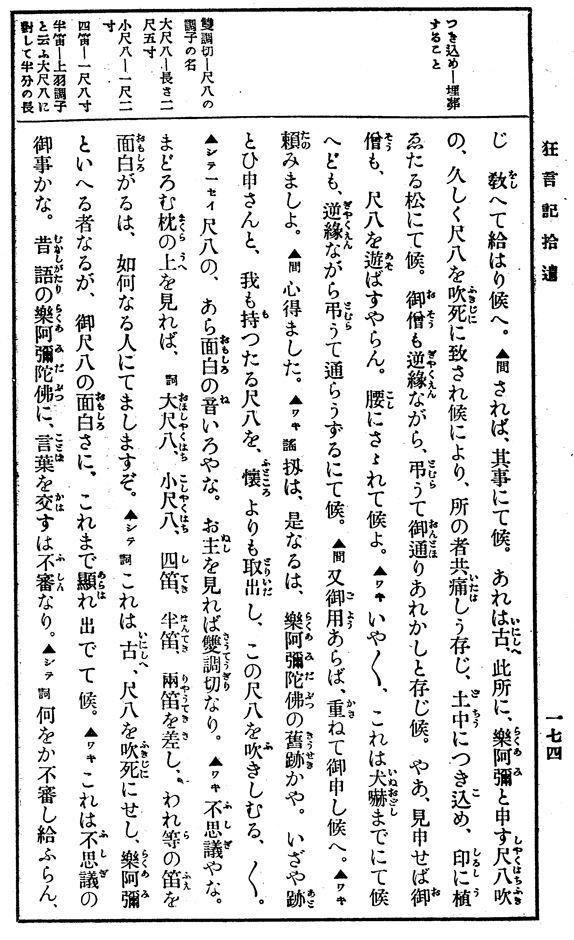

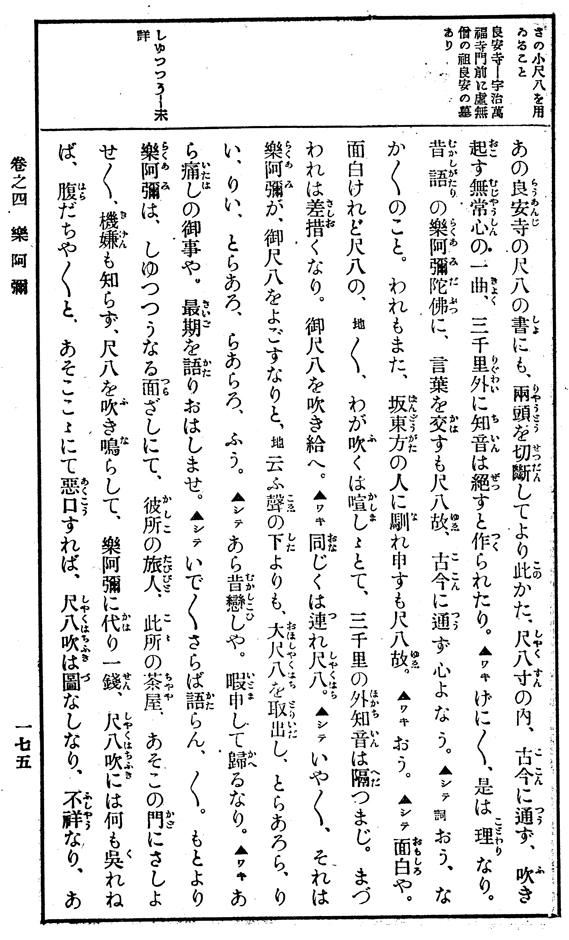

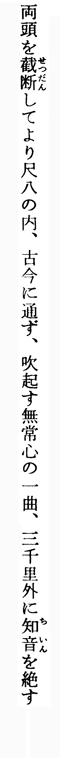

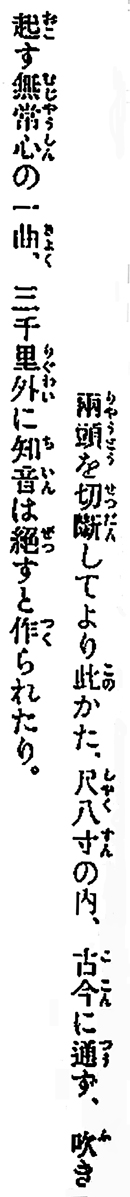

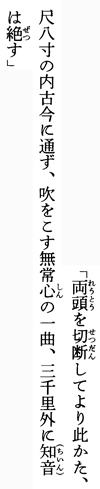

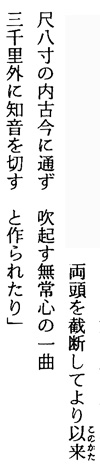

Here the poem in Japanese (cp. four slightly differing printed versions in figures 3, 5, 7, and 9, to the right):

両頭を切断してより此かた、尺八寸の内、古今に通ず、

吹き起こす無常心の一曲、

三千里外に知音は絶す。

- in romaji:

Ryōtō o setsudan shite yori kono kata,

shakuhassun no uchi kokon ni tsūzu;

fuki-okosu mujō-shin no ikkyoku,

sanzenri-gai ni chi-in wa zessu.

A very thorough and detailed study of Rakuami is presented in

Carolyn Martha Haynes' excellent PhD thesis 'Parody in the maikyōgen

and the monogurui kyōgen' (1988).

Her translation of the poem in question reads as follows, as being based on an Izumi School version of Rakuami presented in Nomura & Andō, 1974:

"When both ends are cut, the Middle Way is clear;

One Breath through the flute joins past and present.

In three thousand leagues there will be none

Who understands an enlightened tone."

In her commentary (pp. 104-105) Carolyn Haynes explains as follows:

"The first line, tezukara ryōto setdan shite yori, has a double meaning;

it refers both to transcending the illusion of the duality of existence and the manufacturing the shakuhachi, cutting the two ends of the instrument.

The last two lines imply the rarity of people enlightened enough to appreciate music played with true mujōshin,

an understanding of the impermanence of things.

Thus, for Rakuami and the priest, the boundary between the living and the dead is nothing that love of their art cannot transcend."

Furthermore,

On internationally renowned US kyōgen specialist and performer Don Kenny's comprehensive and very informative website www.kyogen-in-english.com you also find this enlightening translation/rendering of Rakuami's poem - see direct link at web page bottom:

After severing the dragon head, the Shakuhachi is tuned

by playing the Song of Transience, thus made so that

it forms close friendships between those from places

more than three thousand miles apart.

ADDITIONAL COMMENTS OF MY OWN:

Ryōtō, 両頭, commonly translated as "double-sided", or "double-headed",

also carries the meaning of "dual(istic) opposites", such as f.i. Birth versus Death; Suffering versus Relief; Delusion versus Enlightenment (Zengaku Jiten p. 1501).

The term, or concept, of setsu-dan, 截断/切断, to "cut off",

appears as early as in the 10th century, in a poem by the Chinese Zen master Tokusan Enmyō (Zengaku Jiten p. 720).

It is highly probable that ryōtō, lit. "Twin Heads", refers to Fuke Zenji's recorded saying in the Rinzai roku, Ch. 29, 9th century, in which he speaks about the "Bright Head",

明頭, and the "Dark Head",

暗頭,

both of which are to be rejected, it is being proclaimed.

Fuke Zenji who was a Chinese pre-Rinzai Lineage Ch'an/Zen monk may actually, in his myōan 明暗 poem, be polemizing on the 8th century Chinese Sōtō

Zen monk Sekitō Kisen's statements about

明暗 in the famous essay of his, the Sandōkai ...

An alternative, somewhat more sophisticated, interpretation of the Myō-an (or Mei-an) Couple (or Pair): Myōan sōsō,

明暗雙雙, is given in Zengaku Jiten, p. 1397. Here myō (alt. mei) signifies the "discriminate", or "partial",

where as An represents the "indiscriminate", or "impartial".

The renowned Japanese Zen master Takuan Sōhō (1573–1645)

is known to have composed one very comprehensive literary work entitled as follows:

明暗雙雙集, Myōan sōsō shū, "Anthology of Myōan Duality".

The meaning of mujō, 無常, is elegantly explained by Esperanza Ramirez-Christensen in her outstanding book

'Emptiness and Temporality. Buddhism and Medieval Japanese Poetics' (2008):

"Mujō 無常

Mutability or temporality, the coming into appearance and subsequent dissolution of things through the vicissitudes of time; epistemologically related to the absence of an eternal core,

essence, or substance in things, hence their emptiness. Mujō may be said to be one of the principal registers of the Japanese traditional aesthetic sensibility,

both in its privative and ecstatic modes. It is crucial to the experience of compassion, and a fundamental element in the awakening of religious faith."

THE DATE AND TIMES OF 'RAKUAMI'?

Rakuami has survived till today among a total of more than 250 classical kyōgen plays still being performed.

Some Japanese kyōgen authorities do in fact recognize Rakuami as possibly the oldest play in the repertory of the Ōkura School of kyōgen,

believed to have been founded by Konparu Yatarō, active ca. 1532-1555, or perhaps by Konparu Mangorō, ca. 1532-1570.

The title Rakuami first appears in a register of kyōgen plays in the Tenshō kyōgen-bon,

天正狂言本, dated 1576 or 1578 -

it is, however, a popular theory that the play may in fact originate from the dengaku play

Shakuhachi no nō, 尺八の能,

reported to have been performed in Nara as early as in 1446 (Bun'an 3).

Still, the oldest surviving version of the Rakuami text as such has been preserved only in the kyōgen collection Toraakira-bon,

大蔵虎明本, dated as late as 1642,

compiled by the 13th head of the Ōkura School, Ōkura Yaemon Toraakira, 1597-1662.

Then, since 1660, the Rakuami text has appeared in quite numerous editions of the socalled E-iri kyōgen-ki,

絵入狂言記,

'Illustrated Records of Kyōgen'

as well as in a few 20th century kyōgen publications.

EPILOGUE:

Among the many old Fuke Shakuhachi textual sources preserved at the Myōan-ji in Kyōto, one especially fascinating document is entitled

Kyorei-zan engi narabi ni sankyorei-fu ben,

虚霊三縁起並ニ虚霊譜辯,

"Lecture on the Origin of the Empty Spirit Mountain [i.e. the Kyōto Myōan-ji] and the Three Empty Spirit Music Pieces [i.e. Mukaiji, Kyorei & Kokū]".

Dated 1737, Kyōhō 22, 9th month, this hand-scroll bears the signature of Kandō Ichiyū, 寛堂一宥,

18th abbot in the traditional Myōan-ji lineage, who died in 1738, Genbun 3, 2nd month, 23rd day (Nakatsuka Chikuzen, 1979, pp. 133 & 150).

Quoting from that text:

虚竹有投機偈云、

一従截断両頭後、

尺八寸中通古今、

吹起無生真一曲、

三千里外絶知音、

"Kyochiku had [or, favoured] a speculative Buddhist verse,

which says,

"When all Dualistic Thinking is eliminated,

the shakuhachi dissolves the distinction between Past and Present.

That one unique sound of the True Reality of the Non-born

brings even the Purest of Wisdom [Skt.: Jnana] to an end,

without limit."

Do note that 無生真 here, and 無常心

quoted previously, are homonyms, both being pronounced as mu-jō shin.

However, their meanings do in fact differ: A "mind of impermanence" and "non-born true reality", respectively.

Perhaps the author of the Kyorei-zan engi only knew the original poem from hearsay, or - he may deliberately have changed the two characters?

The Kyorei-zan engi text continues,

嘗虚竹在城州宇治、号朗菴主、命終樹塔於宇治郡五箇庄中、

人呼為普化塚也。

"Once Kyochiku stayed in Uji in Jōshū [mod. Kyōto Prefecture] he called himself 'Rōan the Hermit'.

By the end of his life he erected a five-levelled monument

[a 'gorintō' grave pagoda?] in the vicinity of Uji.

People call it 'The Grave of Fuke'."

This is how legends are created, 'history' fabricated/invented - through the cunning manipulation of quotations from scriptures of the past ...

Torsten Olafsson - March 2010. Revised in May 2017

BIBLIOGRAPHY - specific:

Christopher Blasdel & Kamisangō Yūkō:

The Shakuhachi. A Manual for Learning.

Printed Matter Press, Tokyo, 2008. Pages 78-80.

Hashimoto Asao & Doi Yōichi, eds.: Kyōgen ki.

Shin Nihon koten bungaku taikei, Vol. 58,

Iwanami Shoten, Tokyo, 1996. Pages 541-542.

Carolyn Martha Haynes: Parody in the maikyōgen

and the monogurui kyōgen. Ph.D. thesis.

Cornell University, 1988. Pages 102-131 & 268-271.

Available online at https://secure.umi.com

Cat. no. AAT 8804579.

Ikeda Hiroshi & Kitahara Yasuo, researchers & editors:

Ōkura; toraakira-bon kyōgenshū no kenkyū,

大蔵虎明本狂言集の研究.

"A Study of the Ōkura; toraakira-bon kyōgenshū."

Vol. 2. Hyōgensha, Tokyo, 1973. 3 volumes.

Original work published in Kyoto, 1642.

Riley Kelly Lee: Yearning for the Bell: A Study of

Transmission in the Shakuhachi Honkyoku Tradition.

Ph.D. thesis, University of Sidney, 1992. Ch. 3.2.1.

Accessible online at: www.rileylee.net/thesis.html.

Nakatsuka Chikuzen: Kinko-ryū Shakuhachi Shikan.

Nihon Ongaku-sha, Tokyo, 1979. Pages 133 & 150.

Nishiyama Matsunosuke: Iemoto Monogatari.

Chūō Kōronsha, Tokyo, 1976. Pages 162-164.

Nomura Hachirō, ed.: Kyōgen-ki. "The Book of Kyōgen."

2 vols., Yūhōdō Shoten, Tokyo, 1917. Vol 2: Pages 173-176.

Nomura Kaizō and Andō Tsunejirō, eds.: Kyōgen Shūsei.

Shun'yōdō, 1931. Revised and expanded edition

published by Nōgaku Shorin, 1974. Pages 511-512.

I have not yet been able to obtain a copy of this book.

Ōkura Yaemon Toraakira: Toraakira-bon.

8 vols., Kyoto, 1642. 237 kyōgen plays.

Torsten Olafsson: Kaidō Honsoku, 1628: The Komosō's Fuke

Shakuhachi Credo. On Early 17th Century Ascetic Shakuhachi

Ideology. Publ. by Tai Hei Shakuhachi, California, 2003.

Includes a CD-ROM with the author's complete M.A. thesis on

the same subject.

University of Copenhagen, Denmark, 1987.

Purchasable at www.shakuhachi.com.

Thesis pages 108 & 131.

Esperanza Ramirez-Christensen: Emptiness and Temporality.

Buddhism and Medieval Japanese Poetics.

Stanford University Press, Stanford, California, 2008.

Page 186.

A.L. Sadler: Japanese Plays. No-Kyogen-Kabuki.

Translated by A.L. Sadler, M.A.

Argus & Robertson Limited. Sidney, 1934. Pages 124-126.

A.L. Sadler: Japanese Plays: Classic Noh, Kyogen,

and Kabuki Works. Translations by A.L. Sadler,

with a new foreword by Paul S. Atkins.

New edition published by Tuttle Publishing, 2010.

Sasano Ken, editor (1901-1961): Kohon nō kyōgenshū, Vol. 2.

4 vols., Iwanami Shoten, Tokyo, 1944.

Link: http://dl.ndl.go.jp/info:ndljp/pid/1125621

Takahashi Kūzan: Fukeshū-shi. Sono shakuhachi sōhō no gakuri.

Fukeshū-shi kankōkai, Tokyo, 1979. Page 31.

Toyohara Sumiaki (1450-1524): Taigenshō (compl. in 1512), 13 vols.

Nihon koten zenshū kankōkai, Tokyo, 1933.

I have not yet been able to obtain a copy of this book.

A digitalized version of an 1841 edition of the Taigenshō

preserved in The Library of Congress in Washington

is offered for free download at this web address:

www.archive.org.

The link to the downloadable PDF does, however, direct you

to a text in German, not to the Taigenshō file.

Two editions of the Taigenshō are preserved

in microfilm format at the Library of the Imperial

Household in Tokyo.

Ueno Katami: Shakuhachi no rekishi. Shimada Ongaku Shuppan,

Tokyo, 1983, Pages 162-163 && 213-215.

New edition publ. by Shuppan Geijutsu-sha, Tokyo, 2002.

Zengaku Jiten, ed. by Jimbo Nyoten & Andō Bun'ei,

Shōbō Genzō Chūkai Zensho Kankōkai,

Tokyo, 1962. Page 1501.

INTERNET REFERENCES - specific:

Don Kenny: Kyōgen in English:

Kyōgen in English: The dance-kyōgen 'Rakuami' translated

尺八と一休語りの虚無僧一路

Weblog focusing on 'Shakuhachi, Ikkyū, Komusō' and - Rakuami.

平成の虚無僧一路の日記

Webblog focusing on 'Komusō in the Heisei Period' and - Rakuami.

SELECT BIBLIOGRAPHY - general:

Carolyn Haynes: 'Comic Inversion in Kyōgen:

Ghosts and the Nether World.'

The Journal of the Association of Teachers of Japanese,

Vol. 22, No. 1 (April 1988), pp. 29-46.

Available online at www.jstor.org

Carolyn Haynes: 'Parody in Kyōgen:

Makura monogurui and Tako.'

Monumenta Nipponica,

Vol. 39, No. 3 (Autumn, 1984), pp. 261-279.

Available online at http://www.jstor.org

Don Kenny: The Book of Kyōgen in English.

Dramabooks (Geki Shobō), Tokyo, 1986.

Fourteen kyōgen songs and six plays.

Don Kenny, comp.: The Kyōgen Book:

An Anthology of Japanese Classical Comedies.

The Japan Times, Tokyo, 1989. 31 plays.

Don Kenny: A Guide to Kyōgen.

Tokyo: Hinoki Shoten, 1968; 4th ed. 1990.

Synopses of all plays in the repertoire and a brief introduction.

Dorothy T. Shibano: 'Suehirogari. The Fan of Felicity.'

Monumenta Nipponica, Vol. 35, No. 1 (Spring, 1980), pp. 77-88.

Available online at www.jstor.org

DVD:

Tōjirō Yamamoto Dynasty:

Kyōgen of the Tōjirō Yamamoto Dynasty

10 CD set including "Rakuami" (Ōkura-ryū).

Published in May, 2007.

Available from Far Side Music - item no. FSV3299

www.farsidemusic.com/acatalog/NOH.html

Tōjirō Yamamoto Family performance in Indonesia

Tōjirō Yamamoto Family performance in Indonesia

| To the front page | To the top |

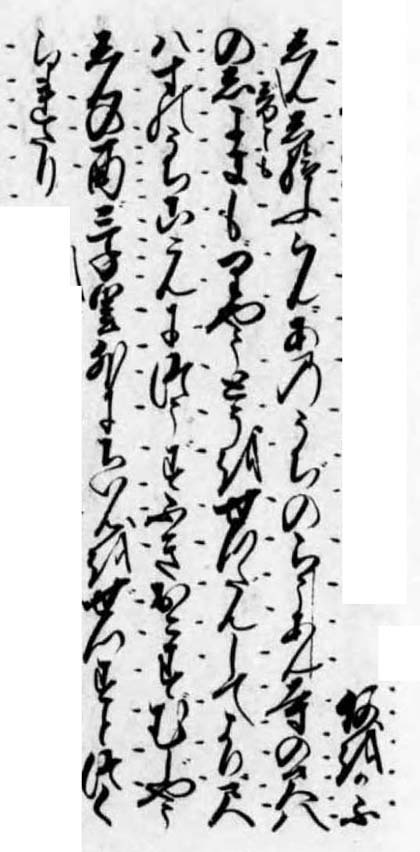

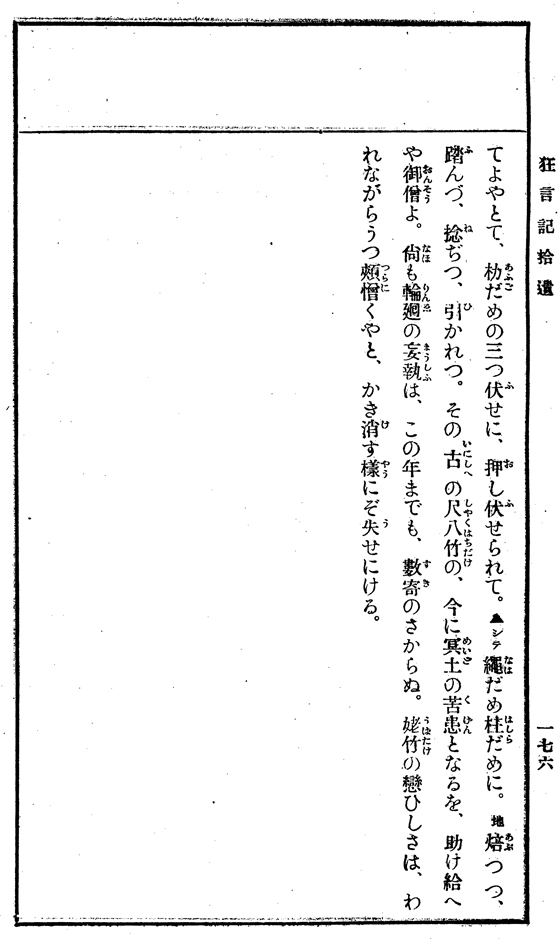

Figure 0

'Rakuami' poem:

"Reject Dualism".

Ōkura Toraakira-bon

Kyōgen-shū, 1642

In Ikeda & Kitahara, 1973

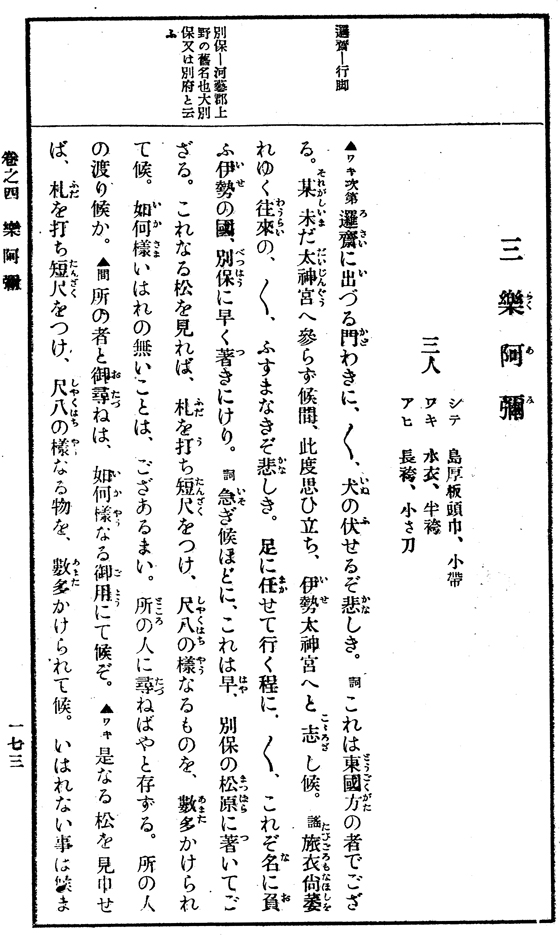

Figure 1

"Ō-shakuhachi"

"Ko-shakuhachi"

"Shiteki"

"Hanteki"

"Ryūteki

Figure 2

"Rōan-ji no

Shakuhachi

no sho"

Figure 3

Rakuami poem

Nishiyama

Matsunosuke

1976 edition

Figure 4

Two Ikkyū poems

in the Taigenshō, 1512

At least acc. to

Takahashi Kūzan

1979 edition

Figure 5

Rakuami poem

Kyōgen-ki

1917 edition

Figure 7

Rakuami poem

Kyōgen-ki

1996 edition

Figure 9

Rakuami poem

Ueno Katami

1983 edition