|

After ca. 1665? to 1795: The Kyotaku denki Original Text,

1981 edition, the Kyotaku denki kokujikai Illustrations,

and Tsuge Gen'ichi's 1977 Translation

虚鐸傳記 / 虚鐸伝記国字解

- Kyotaku denki / Kyotaku denki kokujikai

WARNING! The Kyotaku denki narrative is complete fabrication that cannot be taken seriously as trustworthy "historical fact" in any way.

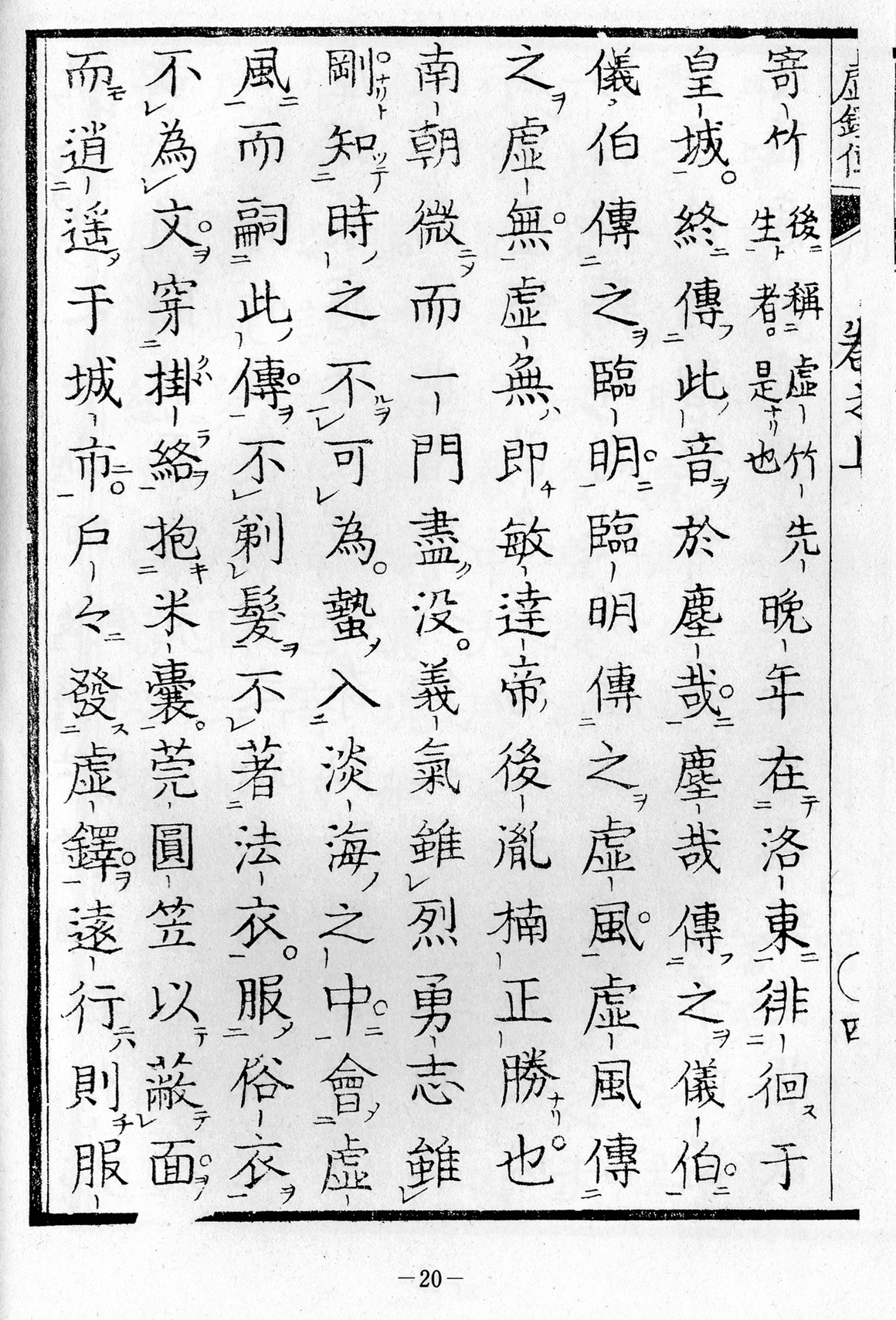

The KYOTAKU DENKI TEXT in the KYOTAKU DENKI KOKUJIKAI EDITION of 1795,

edited and publicized in Kyōto by YAMAMOTO MORIHIDE, late 18th century.

Acc. to the very opening paragraph of the Kyotaku denki, the author and tale teller was a certain 'Ton'ō',

遁翁,

who was, allegedly, a monk active during the Kan'ei Periode, 1624-1644.

But we know of no existing biographical data in existence regarding any such "historical personality", whatsoever.

There is, however, very little, if anything, in the text of the Kyotaku denki that indicates it was thought out and saved to paper

by any class of ordained Buddhist monk.

Much more likely, the text would actually have been produced by one or more sufficiently learned masterless samurai, socalled 'rōnin',

who attempted to organize and fraudulently legitimize the komusō lay beggar monks in the area in and around Kyōto, beginning

during the last decades of the 17th century.

Primus motor in that process was no doubt a group of 'komusō' of the Kyōto Myōan Temple, a socalled "temple" that was definitely first established

during the last few decades of the 1700s!

In any case, Kyotaku denki was indeed, eventually, published in Kyōto, in 1795.

It is important to note, that of all the numerous Chinese and Japanese individuals mentioned by "name" in Kyotaku denki,

only three of those - perhaps even only two? - are known to have ever lived, namely:

The 13th century Buddhist monk Shinchi Kakushin, 1207-1298, and the samurai army leader Kusunoki Masakatsu, second half of the 14th century.

One should actually question whether Fuke Zenji, 9th century, was ever a real "living human being" ...

Kyotaku denki is mentioned, quoted, and praised, over and over again.

But probably only few know how many non-truths and "impossibilities" are actually contained and expressed in the text.

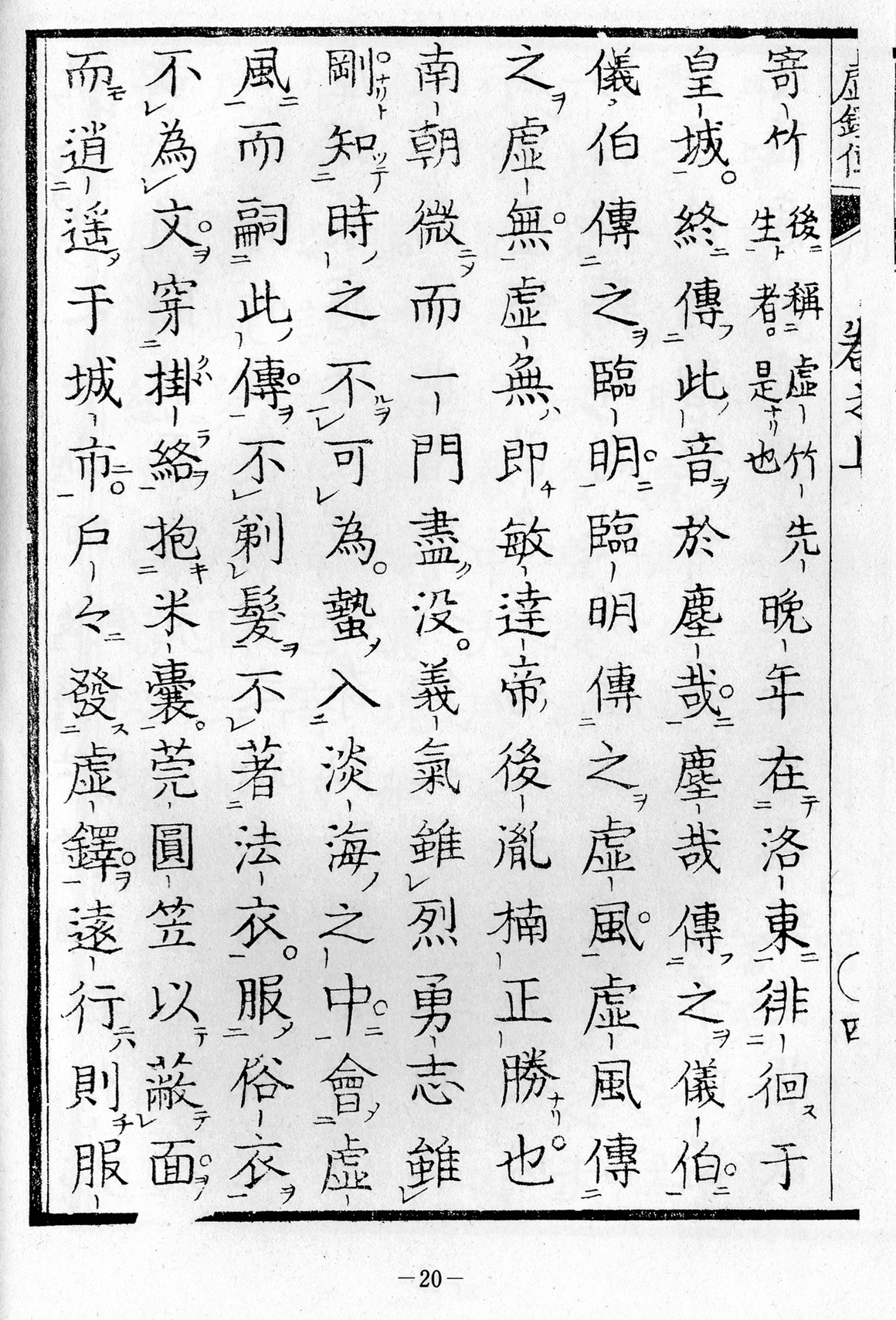

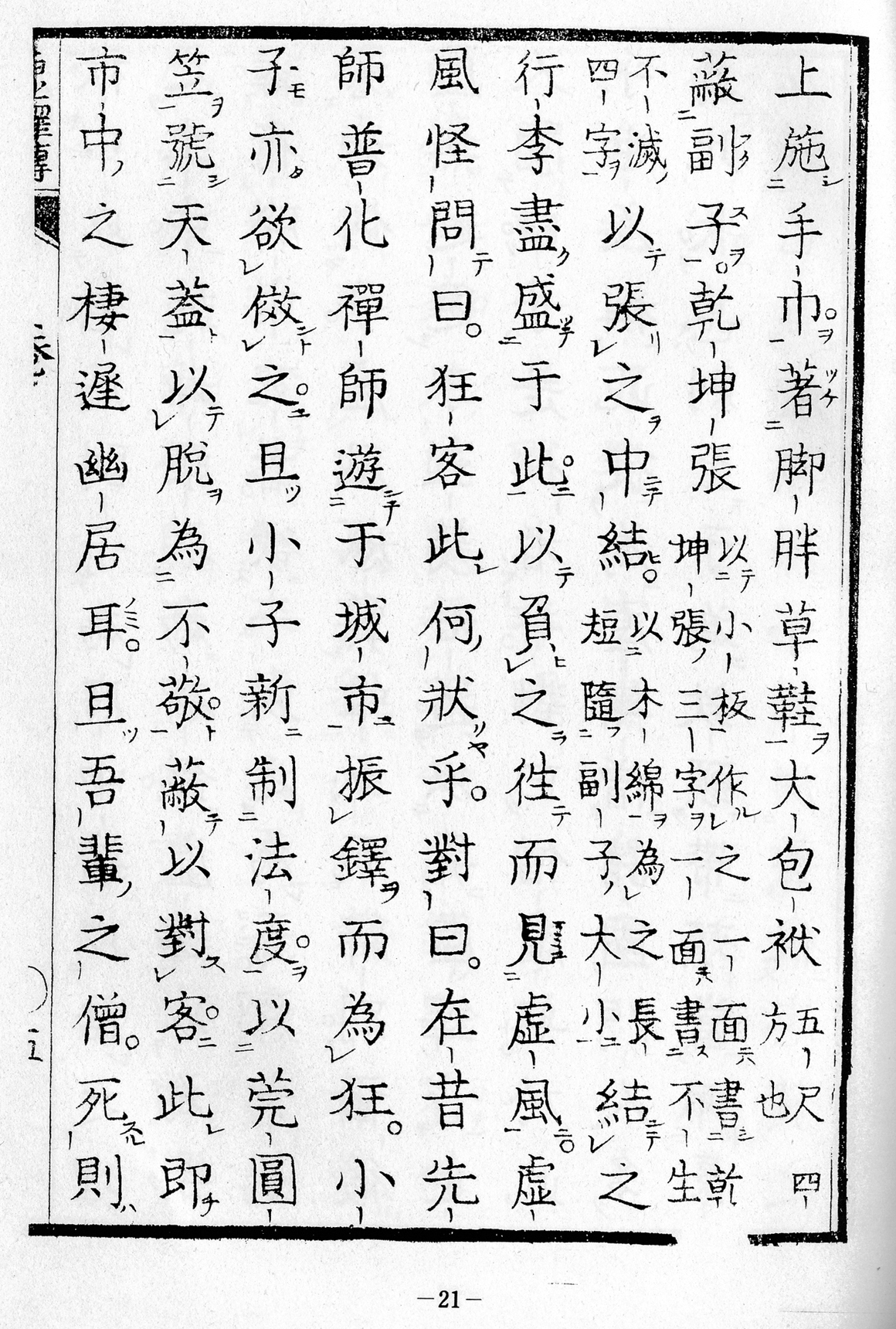

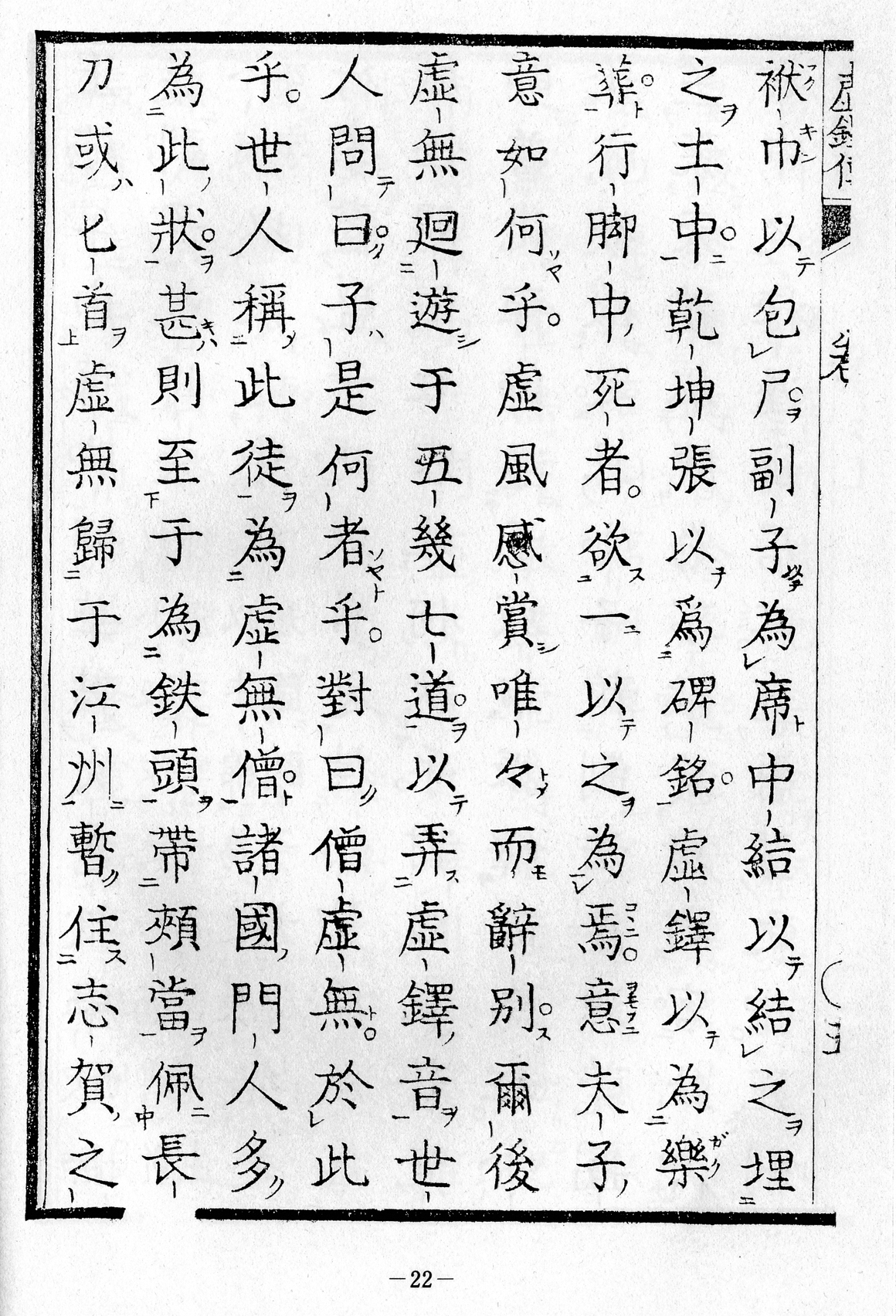

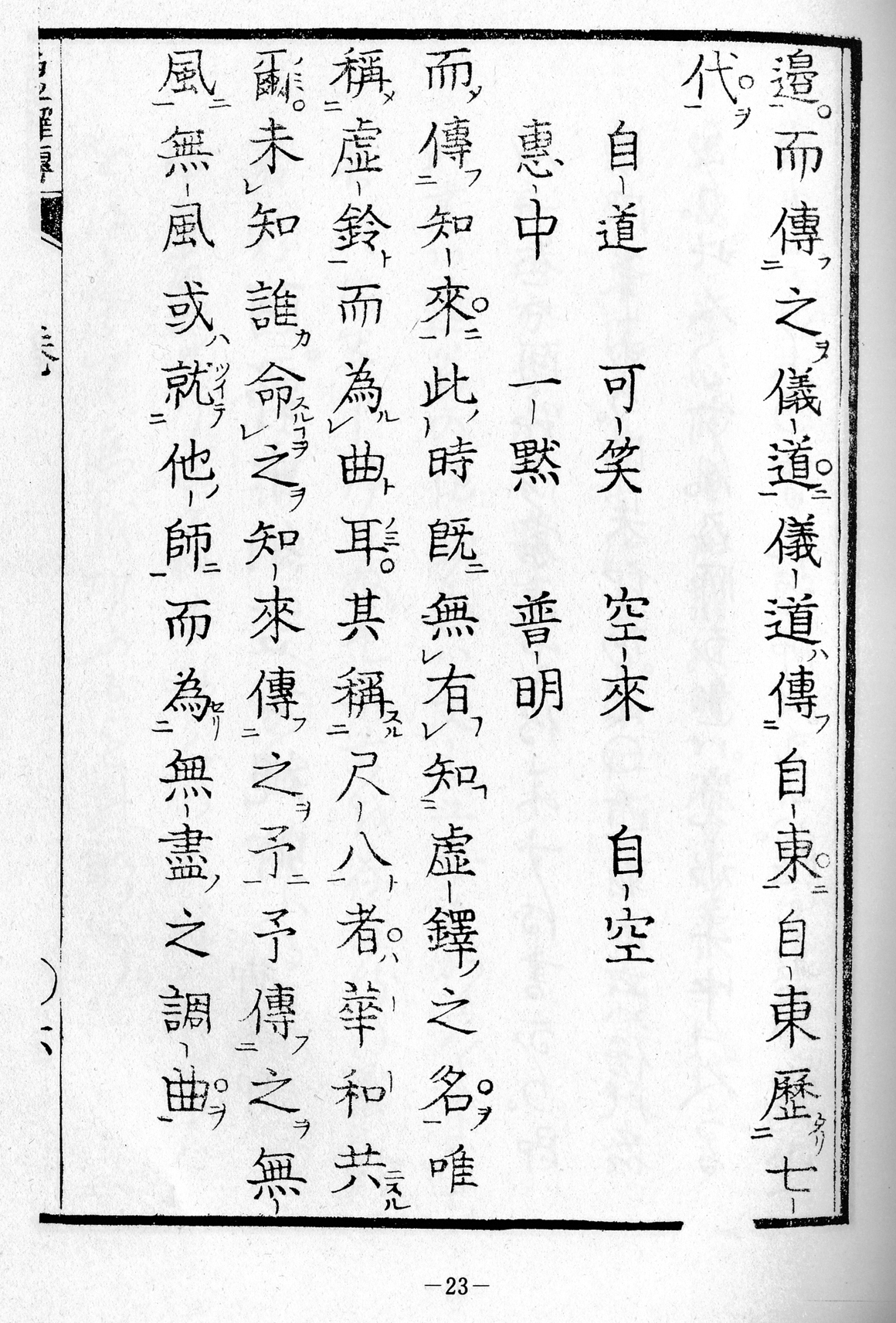

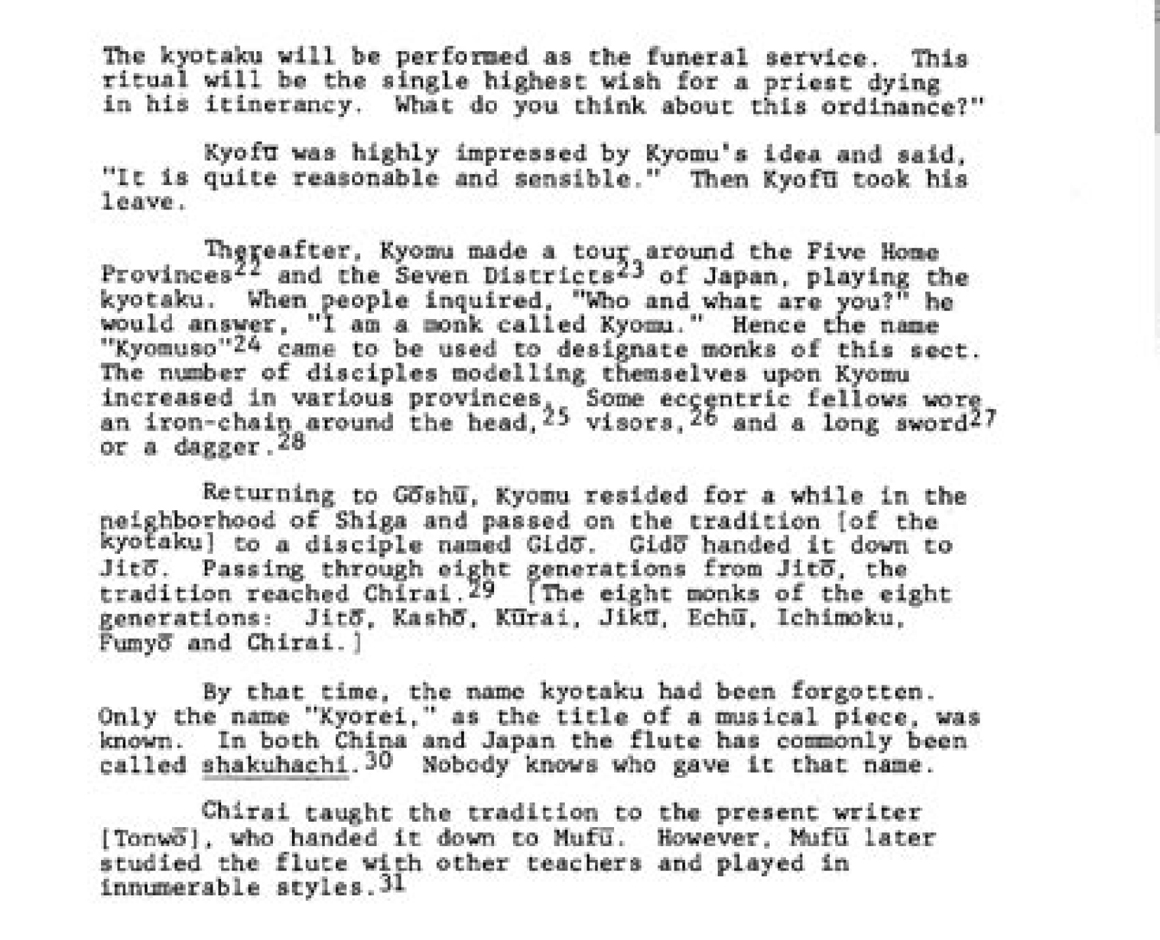

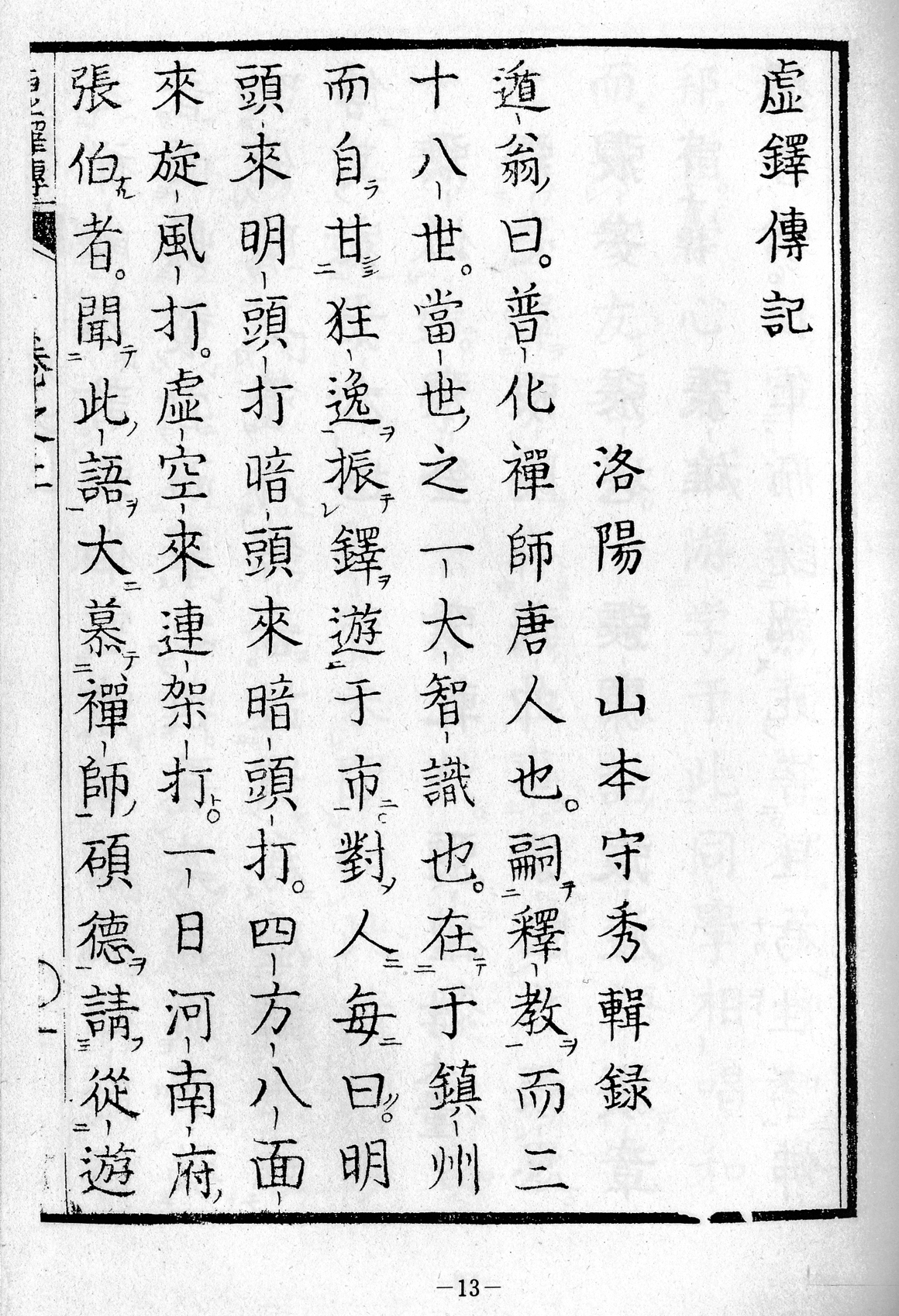

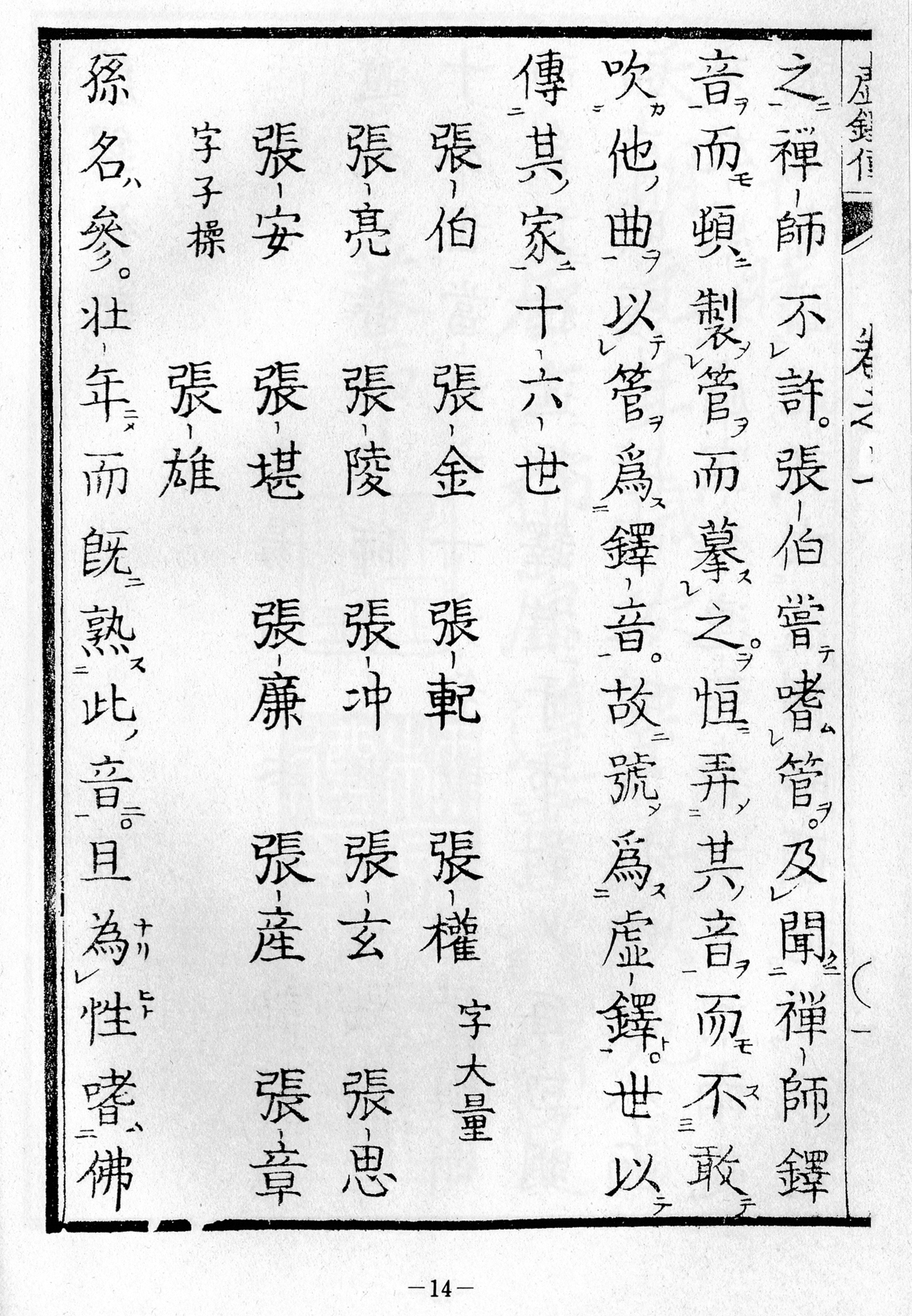

Here follows the reproduction of the Kyotaku denki text in the important, by now very rare 1981 publication edited by Kowata Suigetsu, 1901-1983, on pages 13 through 24:

The 'Kyotaku denki' in Kowata Suigetsu's 1981 edition, pp. 13-24

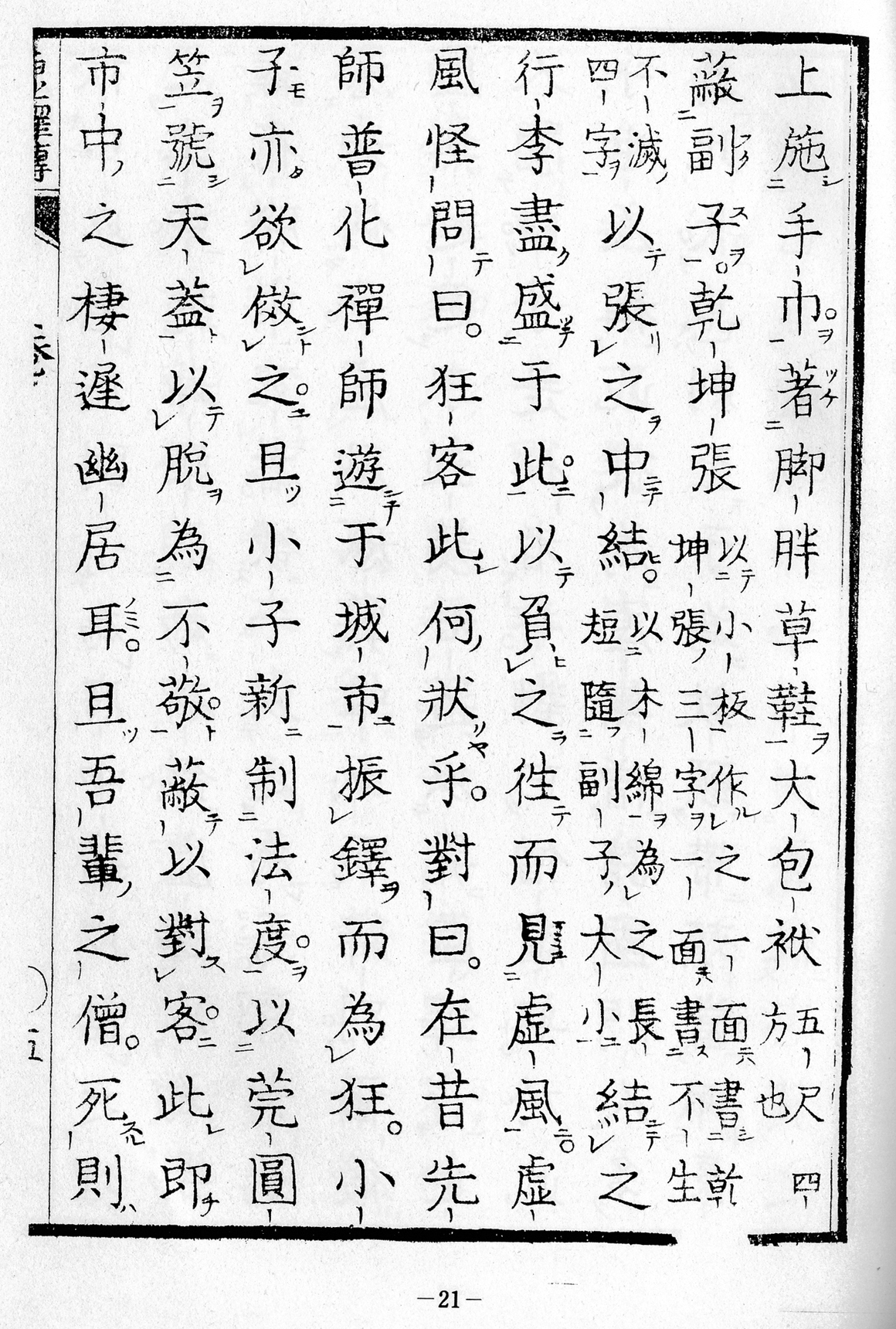

The ILLUSTRATIONS in the KYOTAKU DENKI KOKUJIKAI, Kowata Suigetsu Edition, 1795/1981

'Kyotaku denki kokujikai', 1795:

Here, the illustrator shows us how, supposedly, Fuke's walking in the streets while ringing his beggar's bell inspired a never having existed "Chang Po", Jap.: 'Chō Haku',

to create the solo flute piece 'Kyorei'.

'Kyotaku denki kokujikai', 1795:

The picture shows Shinchi Kakushin on his way in an ocean going sailboat to study

Zen Buddhism in China, mid-13th century.

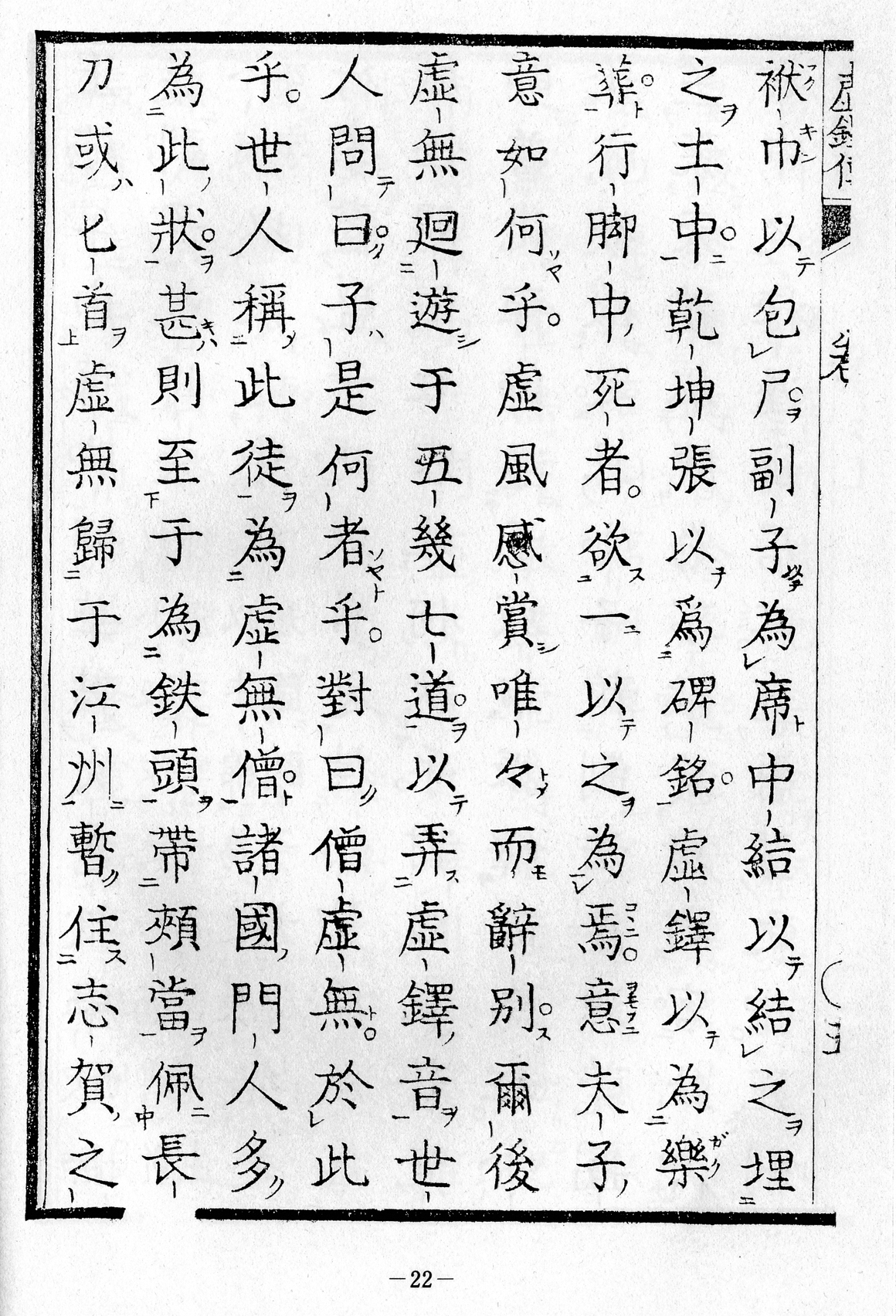

'Kyotaku denki kokujikai', 1795:

Truly so, Kakushin returned from China, in 1254 - here approaching land

near Hakata on Kyūshū.

Interestingly, Hakata is the hometown of the sub "temple" of Kyōto Myōan-ji

named Itchōken, a small provincial ascetic shakuhachi center that

was actually only established there late in the 17th centuiry, at the earliest.

'Kyotaku denki kokujikai', 1795:

This is the moment when Shinchi Kakushin presents his Japanese student, the legendary 'Kichiku', with the flute that he supposedly brought with him back from China

in 1254 - that is: certainly only according to the legend!

'Kyotaku denki kokujikai', 1795:

This is when, relates the legend, Kichiku receives the solo piece 'Mukaiji' in a dream

- later having his master Kakushin give the tune that title ...

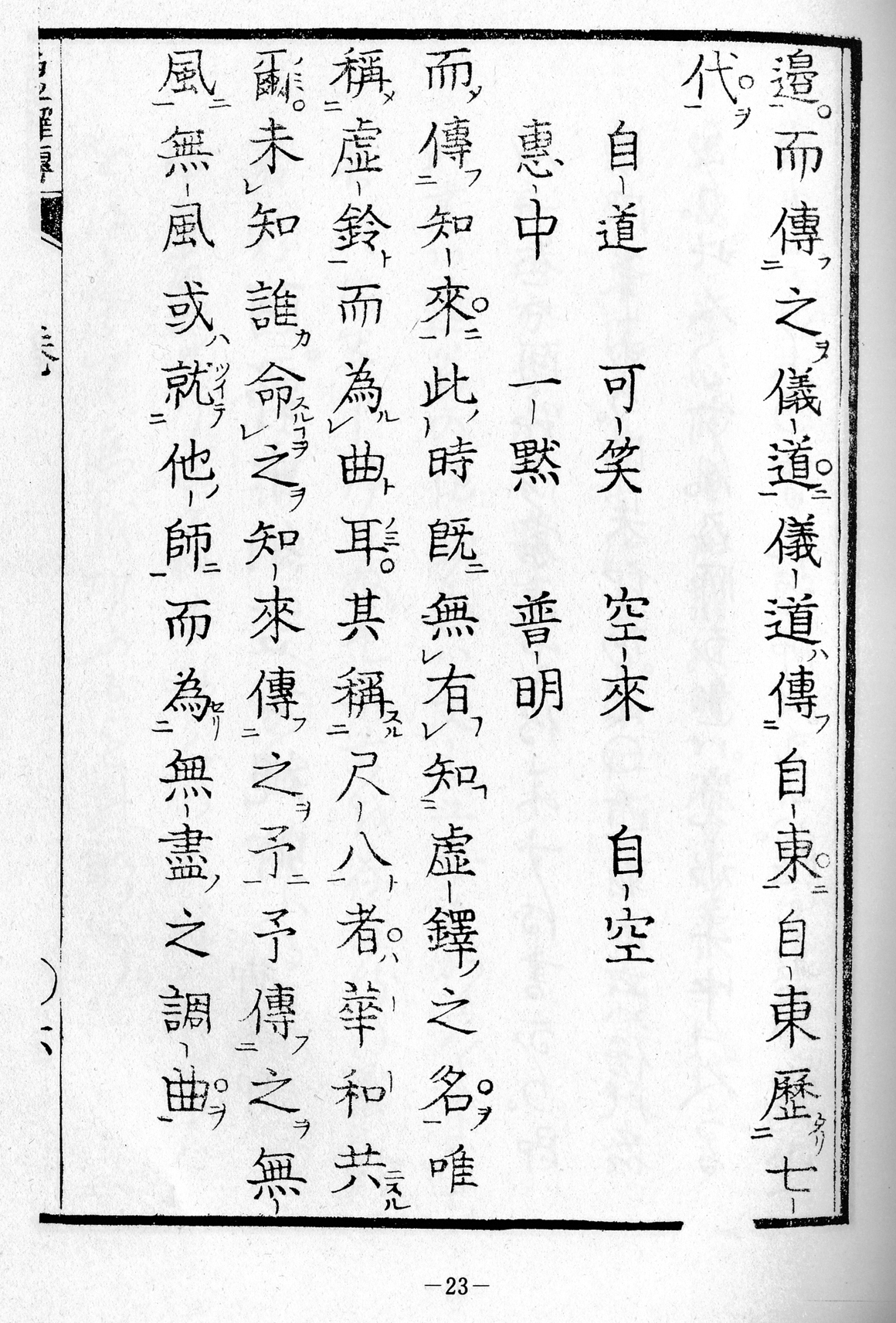

'Kyotaku denki kokujikai', 1795:

In this scene, the legendary ascetic flute practice transmitter named 'Kyōfū' first meets the 14th century samurai general Kusunoki Masakatsu who is known, in real life, to have lost his last, decisive battle in 1399.

Masakatsu then simply having disappeared, the mid-17th century komusō conspirators could therefore "easily adopt" him into their growing shakuhachi player movement

and beggar monk ranks:

In the Kyotaku denki, Masakatsu was given the new name 'Kyo-mu',

虚無,

thus honoring him as the very first albeit "pseudo-historical" 'komusō' of samurai heritage,

虚無僧

- that is, of course: only legendarily.

And, as acc. to Wikipedia Masakatsu died already on January 31, 1400, he would have had very limited time to wander and spread any ascetic shakuhachi gospel.

'Kyotaku denki kokujikai', 1795:

In this concluding illustration we are expected to appreciate Kyōfū sending his disciple Kyomu off on pilgrimage along the 'Tōkaidō' Eastern Coastal Highway.

Kyomu is shown dressed and equipped in a way that would have been completely unthinkable around the year 1400, and even afterwards:

The thick "root-end 'shakuhachi' flute only appeared late in the 17th century.

The 'tengai' braided basket hat only reached that shape and design towards the end

of the 18th century.

The long samurai sword was never to be carried by the wandering, mendicant 'komusō', who were only allowed to bring along with him a short dagger for protection and for practical purposes.

Less than a handfuld of early 17th century pictures of 'Fuke-komosō' are seen to show flute players with shallow basket hats and long swords!

Anyhow, summing up: There were not at all and in no way any 'komusō' in action until past the middle years of the 1600s. And highly reputed historical figures like both Fuke, Shinchi Kakushin and Kusunoki Masakatsu were simply taken hostages in order to glorify and falsely legitimize a faked 'komusō' origin and fully fabricated early, pre-Edo Period "ascetic samurai shakuhachi history".

TSUGE GEN'ICHI's 1977 TRANSLATION of the KYOTAKU DENKI SECTION of the KYOTAKU DENKI KOKUJIKAI

This translation of the Kyotaku denki kokujikai, 1795, was printed in the N. American music magazine Asian Music in 1977.

On this web page, however, both Tsuge Gen'ichi's introduction, his notes and comments, and the handwritten kanbun/Chinese text have been left out.

Do go to the Asian Music website or to JStor to purchase the full article.

It must be noted, by the way, that Tsuge Gen'ichi appears to have translated the Japanese language version of Kyotaku denki, i.e. the Kyotaku denki kokujikai,

not the older Chinese language, or 'kanbun', version of the document.

Link to Yamaguchi Raimei's Japanese, 'kun'yomi', version of Kyotaku denki text:

Yamaguchi Raimei: 'Kyotaku denki' text

|

|